Today Amy sits down with Yemoja priestess Iya Omigbeni to talk about Isese, Yoruba Ifa, how Witch Trials and cishet-patriarchy impact the practice of spirituality in black/afro-decended communities in the diaspora, the multiplicity of motherhood, dreams, accountability, and the deep magic of water.

Her priestess name Omigbemi means The Water Carries Me, and she gives us some advice about how to connect with waters in our lives.

Omi shares sacred knowledge of the Iyami, arbiters of planetary justice and the source of all creation. She says, "The Iyami is in all of us."

Listen now, transcript below:

Omi is an initiated Yemoja priestess, writer and river keeper committed to caring for the waters and the children of the Earth. She has been a custodian of the shrine of Yemoja, the Mother of All Waters, since 2022 and a student of Ifa since that time.

Outside of her esoteric practice Omi, a self-described 'card carrying lesbian' primarily works alongside queer and trans communities, restoring sacred spiritual knowledge and re-calibrating people in her community to the time-enduring knowledge of the Earth.

Find Omi on instagram @bluesemiotics

Omi recommends the book Mami Wata: Africa's Ancient God/dess Unveiled

TRANSCIPT

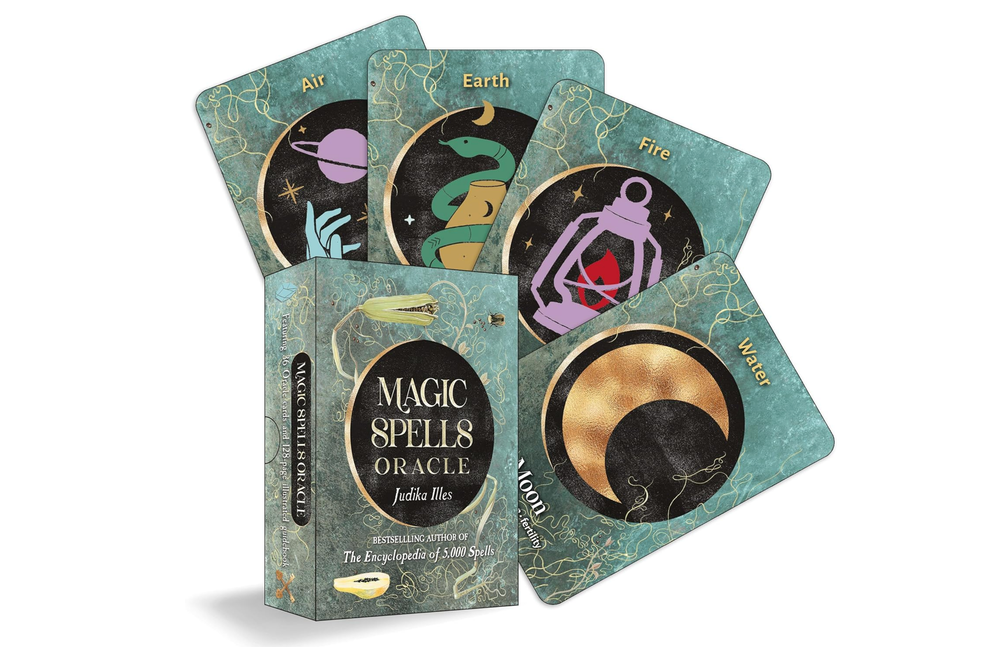

Amy: If you want to support the Missing Witches Project, join the coven. Find out how at missingwitches.com. Or buy our books, new Moon Magic and Missing Witches. And check out our deck of Oracles The Missing Witches Deck of Oracles.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Missing Podcast. No, it's here. It's not missing. It's here. It's the Missing Witches Podcast. Y'all know, I think I start every episode with some kind of disaster. I think last time I knocked over my keyboard and my tea just as I was opening.

Amy: And I like to leave that in because y'all, I'm not perfect. You're not perfect. Let's be a sacred mess together. And not on that note, because she is not a mess. She is gorgeous and perfect and beautifully put together. Please, Coven, welcome Iya Omigbemi. Omi is an initiated Yemoja. Priestess, writer and river keeper, committed to caring for the waters and the children of the earth.

Amy: She has been a custodian of the Shrine of Yemoja, all, the mother of all waters, since 2022, and a student of Ifa since that time. Outside the esoteric practice, Omi primarily works alongside queer and trans communities, restoring sacred spiritual knowledge and recalibrating people in her community to the time enduring knowledge of the earth.

Amy: Hi Omi! Omi, welcome.

Omi: Thank you for that introduction. Um, that was a very beautiful introduction. Thank you. Hi everyone. I'm very happy to be here. I'm so excited to share what I've been studying for a long time. It feels like I'm in school. It feels like I'm in college, like studying the Orisha and studying the knowledge of, of the river.

So I feel, I feel very excited to share what I've learned so far.

Amy: It is. I mean, there are so many people who think that spirituality is just a feeling, or just an emotion, or just a calling, but there really is, like, a depth of knowledge, especially in Ifa, especially because of the attempted erasure of of this sacred knowledge that, um, I love to talk to people who have gotten in depth into this practice.

Amy: Is there anything you want our listeners to know about you before I dive into our questions?

Omi: Yes. I actually want people to know that I myself, even though I do practice this tradition, I trace at least the last 400, 500 years of my family to Jamaica. So I'm also a guest on this land. I'm a guest in Tiohtià:ke and I'm very happy to be here.

Omi: This land has been very grateful for me. I mean, has been very generous to me as opposed to people. I'm very grateful for the land. Um, and so I'm also reclaiming this tradition that has been. Lost, covered up, hidden for a very, very long time. So it feels very, um, beautiful, I think, to share with those who may listen and those who may connect.

Omi: Whether they're Jamaican, whether they have an interest in Sheshe or Ifa or Yemoja. She's an extremely popular Risha. She's, she has a very, a very wide net. Um, pun intended. Um, but. Hey. So I would say, yeah, that's me.

Amy: And you mentioned Tiohtià:ke, and for those of you who are listening, that's like the original name of Montreal.

Amy: So I'm especially excited to be sitting here with a local witch. We're always talking about supporting our local witches, and now I have one right in front of me. Um, what is Isese? Let's start there.

Omi: So Isese is the name of the traditional spiritual practice of the Yoruba people. And the Yoruba people are, more accurately, they're not confined to Nigeria.

Omi: They're spread out between Benin, Togo, and Nigeria, of course. And so, it really utilizes the oracular system called Ifa, it's called Fa in other places as well. So, Ewe Vodou also utilizes this oracular system. Um, but to talk a little bit more about it specifically, it is an extremely vast library, I think, of knowledge that contains 256 chapters of like, My Oluwo, my teacher, and I also want to take a moment to shout out my teachers, Ifa Oluwo, my, my Adeola, also known as Marshall Hare, and my Olori, Ifa Abunmi Adetutu Efuntuola Eshintoi Omonujogun Egbetokumbadiola, she has a lot of names, she's very important, um, who have guided me through a lot of this knowledge.

Omi: I wish I had said this first, but I digress. Um, so yes, so IFAW is itself a combination of 256 chapters. of sacred knowledge that has been compiled, some people say between 000 years. They are extremely dense. And for anyone to be considered a competent Babalawo, you have to study for at least 15 years. Um, I am not a Babalawo.

Omi: I'm not yet an Ifa. I, I would like to initiate, I mean, I have to initiate into Ifa soon, but I'm taking my time. Studying Yemoja is already very deep in and of itself. And so, I've seen some people also refer to IFA as being a type of computer. Um, Jujube, who is also someone that I know, her initiated name is Oshun Fumilola.

Omi: And so she's a priestess of Oshun, and she, um, has talked about it being a sort of ancient technology, and I would think that's, like, the perfect language to describe what Ifa itself is. So it has a very expansive reach, also, I think, you know, having come to the Americas through the people brought to countries like Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Brazil, the big one, Trinidad, um, And within the Ashesi Pantheon of Deities, there exists 401 Arisha, of which Yemoja, who is my tutelary deity, um, but the 401 number also reflects that new Arisha are constantly being made.

Omi: So let's say you and I, we live amazing lives, we do amazing things, we have perfect spotless character, then we go on to become Arisha ourselves. And I think that is one of the most beautiful things about this tradition is how divinity is inherent in everyone and possible. So there's so many other Rishas that I could go into, Oshun, Olokun, Ogun, Obatala.

Omi: I wanted to shout them out because I work with them too. And deities can be like, why didn't you mention me? So I wanted to, I wanted to shout them out

Amy: I want to know, um, what, drew you to be so thorough with your research and so, um, intentional with your research. Were your parents involved in this practice or is this something that you have taken up of your own accord?

Omi: That is so funny because my parents, I grew up extremely evangelical. I had to find my way out. I had to find my way out of that. Like, I think it's its own cult, actually. I think we could talk about evangelism as a cult. I'm

Amy: sure we could.

Omi: Yeah, so we, it actually came to me, it had started this whole process or path or journey started for me when I was about 16 and they, spirits just started coming to me in my dreams and my parents at the time they didn't know what to do.

Omi: I didn't know what to do. I was having like ancestors come to me being like, What are you doing with your life? Meanwhile, I'm 16 in high school, just trying to figure myself out. And so that was kind of the beginning, and it died down until I left home to go to university. I went to the University of Waterloo in Ontario, and I was doing a bit of magic here, a bit of magic there, spellcasting, and, but I was, I was successful in some of my spells, but I was also constantly putting myself in danger because my spells, my candle magic, I was doing candle magic, those spells would explode, and I, Yeah, not, not good.

Omi: And so I started getting into tarot, but then for me, like tarot wasn't really, I was also putting myself in danger because spirits would follow me home. No matter like what I said or what I did. I was opening up portals. I think for me, like with the way myself is set up, I don't have anything against tarot or candle magic at all.

Omi: Like I would still do it if the shrine didn't tell me that I shouldn't do it anymore. But, um. But yeah, so that was kind of how I started the path and I think my diligence is just a part of my I always want to know. I'm a little bit nosy. I'm a bit curious. I will ask Yemoja things and she'll be like, that is not your business.

Omi: You don't need to know that. They'll be like, you need to stay human. You're a human being. You don't need to ask like some of these questions. Um, so, and I have amazing elders and my members of my Ile who are also really smart and very intelligent and who I'm always learning from.

Amy: And your Ile of Montreal.

Omi: No, my Ile is actually based in Baltimore, Maryland. So that's another, that's a whole other story. I was very much led. I felt like I was on a string and they were like, come on, like you got to make your way over here. And my Ile is also a really special place because it is one of the very few like openly accepting like Iles of queer people.

Omi: So there's a lot of homophobia and transphobia in this tradition. And patriarchy, as we're going to talk about today has. You know, been really I guess impactful in its reach and also how it's affected our indigenous traditions. And so I'm always so grateful for my Iwe and I always try to shout out the fact that it's so, that it's so queer and trans affirming and accepting because people try to make it seem as if, oh, if you practice ashesha, you can't be gay.

Omi: If you practice ashesha, you can't be queer, you can't be trans. And it's not true. The deities do not agree with that. So,

Amy: yeah, I, I wanted to ask you about, like, why working with queer and trans communities is so important to you, but you kind of already answered that. Can you, like, expand a little bit though, and, um, how you open those doors?

Amy: Do you get a lot of pushback?

Omi: Not publicly. Um, so in Montreal, for the, for the longest time, I was the only person that I knew that practiced Ifa. Um, now I have a few more friends. I have another friend who is very endeared to me. who has also started practicing and other people around me that are interested.

Omi: And I've always been queer. So it was always like, this is my people. This is, this is where I'm at. Like, this is, you know, who I want to serve in a sense. Because I think when I think about also my priesthood and any priesthood, I think. Your priesthood is not about, you know, how you can be helped or how you can help yourself, although that's important.

Omi: It's also about how can this tradition, how can this indigenous knowledge bring forward the people who have been impacted by cis hetero patriarchy and really impacted by racism and all the ways that these systems, you know, interlock to really suppress us and suppress the ashe to use like, um, It's specific language, which basically means like your power, how it just tries to suppress our power.

Omi: So I love my queer people. Like I'm also, I'm a card carrying lesbian myself. Like, so I'm, it's just, There was no other way. And when I think about Yemoja and, you know, the deities and, you know, I won't lie to you. My Jamaican ancestors were like, how are you going to have a baby? Like, you know, they're really concerned.

Omi: Like, how are you gonna like carry on the next generation? I had to be like, well, there are ways, like, I don't want to do that. I tried it, it wasn't for me, like. And so, you know, the spirits also still have their own questions, their own concerns, like, they care about, you know, the next generation. But with Yemoja, she was never bothered by it at all.

Omi: Like, she was like, I don't care.

Amy: Since you bring up the subject of motherhood, I know you want to talk about who the Iyami are in the Yoruba Ise Ise practice, so tell me about that brand of motherhood.

Omi: Oh my god. They are They're very vast, they're very massive, they're very powerful. They are often spoken about in, I think, sort of disrespectful ways because of patriarchy and how patriarchy views female power.

Omi: And so, I really wanted to introduce the Iyami to the Missing Witches community because I think that They, as a figure, as a group, really tie in together the global nature of like the mother goddess and feminine power. And I think that they are so incredibly interesting. So the Iyami also referred to as Awan Iyawa, Iyami Oshironga, Many, many names.

Omi: They have, I think, over a hundred names by which they go by. Um, also they're referred to as the mothers of the night. They can be kind of considered as usually like a group of three maternal, um, figures who serve as the arbiters of planetary justice and the source of all creation. I think that's so metal.

Omi: Like when I learned about them, you know, my Oluo was really like, Yeah, they're really, they're kind of like the police of, of the universe. And I think, you know, police was like, you know, the, the, I think it was like, I don't know if that's the right word, but, um, but they, they are, they are the earth in a sense.

Omi: And so they witness everything and they don't sleep. Like, so they, They are kind of keeping score all the time, and especially they are invested in, you know, protection of the earth and also the protection of women and children, and I think vulnerable and marginalized people as well. They have protected me a lot, they have shown up for me when I, you know, have been abused, or when people have mistreated me, they've always been there.

Omi: And I know that's the case for other people as well. Um, but yes, so kind of go into like Odoo or, you know, traditional knowledge on the Yami. In our tradition, our supreme being, they, and they're also genderless. Um, they are named Olodumare, and they are, that name can mean many things depending on who you're talking to.

Omi: I've seen people describe them, describe the name Olojumare as owner of like the black womb, or I could be wrong, so if someone wants to quote me in the comments, I could be wrong, so don't worry about that. Xochitl people are also very, um, because they're so philosophical, they can be quite like, that's wrong, that's not right, but.

Amy: But there's also like 10, 000 years of oral history that was like the diaspora sort of made it impossible to have concrete definitions in a way, right?

Omi: That's, that's one case. And I think what's true too, that I love about Ifa is that it also talks about many things being true at the same time. There is not just one truth, which I think is really amazing.

Omi: And so back to the Emmy. Uh, they are, they are also considered to be witness to creation and I think that's really cool because when we think about in Christianity, you know, Eve was sort of made from Adam's rib, but here, like in the story of Asheshe, you know, the mothers were very, were there at the very beginning, like they have been there.

Omi: And even in my own. You know, curiosities before my shrines, like I was told, like, the YAMI, they're not even Orisha, like, they are their own category of, like, deity. Um, and, you know, they have a different moral code. Their moral code is not ours. Their moral code is the Earth's. And so sometimes the things that we think, you know, when people say, oh, the YAMI, they're fearful.

Omi: They're fearsome rather. They are, you know, really scary, like all these things. It's like, well, what did you do? Like, you know, because they are not, they're not these like evil beings that I think a lot of us are taught in the tradition or that we see in passing the way that people discuss them. And so, You know, even in Odoo, as I talked about, like, Odoo being, like, chapters of the Thought Corpus, you know, we see stories of them, like, threatening to eat people or, like, actually eating people because they're like, no, I don't, like, why would you do that?

Omi: Why would you mistreat this person? Why would you steal someone's wife? Why would you not take care of the people that you're supposed to be taking care of? We're actually going to punish you for not doing that. Doing what is sacred law. Um, and so I think they disturb our sense of good and evil, especially because they're not male figures such as, you know, deities like Ogun or Batala, who, Ogun particularly, who's spoken about as being very terrifying and doesn't have this overall negative reputation, like, attribute to him.

Omi: Um, where Ogun is described as having red eyes and wears robes of blood. Like, no one is ever, like, talking about Ogun being so terrible. Um, But yeah, so I would, I would kind of describe them in common terms as a chaotic neutral force. And when we think of chaos, if we want to get, you know, a little, a little bit philosophical, when we think about polarities and we think of, for example, in Odoo, there's the Odoo Ejiogbe, which kind of talks about, Light or expansion.

Omi: And then we have the du ku Megi, which is the, like they, those two oos are considered to be the parents of all the 256 oos because of the way their binaries are set up. I don't wanna get too nerdy or too much into the, the, the complexities of things, but, um, and so they kind of represent the darkness. of the universe, like they are the womb of creation, which is a term that I think we see across a lot of different traditions and talking about mother deities is like associating that they are the fertile ground of life.

Omi: And they are both nothing in a cosmic sense, like the blackness, nothingness of outer space. And they're also what allows everything in the world or in the cosmos to exist. Like we all sit in the blackness. Of the universe. So. There's,

Amy: there's something we can relate to here, to that, like, that notion of motherhood, where a mother can be the most caring, tender, or the fiercest, most terrifying, you know, creature in the world, depending on how you come at her, right?

Amy: Exactly. Exactly. You get it. Yeah. And I want to know, um, what's like the selection process for the Ayami? Yeah.

Omi: I think that's a great question. And it's a question that I get a lot as someone who's kind of obsessed with them. I think I'm like, from a from a spiritual, maybe theological perspective. I'm like, they're so they're so boss, like, um, who wouldn't want to be like associated with them.

Omi: But I will say that they are not deities that just exist. Anyone should just decide that they want to talk to you. Um, they are actually highly selective in who they want to speak to. They will actually come to you. Um, they, and that's, that's, I think, like, that's people's experiences. There's another, uh, Um, podcaster who made a podcast called House of Yammy, Ajay, and she talks about it.

Omi: Her name is Buki Fadipe. And so I was listening to her podcast recently, and she was talking about how, yes, like, it was just something that they came to her. And that's kind of how it works. I've seen stories of people who kind of went to go talk to them, and they were not sent for, they were not called for.

Omi: And it kind of led to madness. And so it's very, like, very important, I think, for people to know that they're not a deity that can just be approached. Um, they're very secretive. They're very, they're very loving. I think they're very loving. And they're also very much like, because their power is so awesome and because they're also quite serious, they're almost very clinical, I think, in the way that they move.

Omi: They're like, we kinda don't have time, like, if, if we didn't call for you, please do not come to us.

Amy: So many of our Coven mates have become increasingly obsessed with water. Mm hmm. Philosophize a little bit more for me. Drench me in some of your thoughts about water.

Omi: Oh my god. Uh, this is Yamada's, like, favorite song. Like, So when I first started doing more of my in depth research on water, I was really curious, like, you know, what are the evolutionary beginnings of water, like, where did this thing even come from?

Omi: And it's so abundant. And so I'll combine some of my, like, priestly knowledge here as well. And so, you know, when we look at evolutionary history, water was actually a molecule that existed in outer space before this huge asteroid. Came and pulled it down to Earth's atmosphere where it rained for a thousand years.

Omi: To make the ocean. And so in my tradition, we learned that, you know, before there was any earth or any like, like soil or dirt for us to make our lives on. It was just the domain of Olokun, who is the orisha of the ocean. And Olokun, Is a primordial being, is very old. And when they decided to bring humans here, she was actually kind of pissed.

Omi: She was like, nobody thought to ask me before you came. Like, this is my home. This is my domain. Why, why'd you bring people here? And so, you know, in like, history, like religious history, we see, The ocean, you know, beings coming out of the ocean to teach us things, to teach us how to be human, how to care for one another, how to love one another, how to establish democracy, how to establish bureaucracy.

Omi: The water is, is everything. It is the foundation of us all, I think, as a Caribbean person. As someone who's descended from enslaved people, I think a lot, like, the water is in a sense, like, one of my very first ancestors. My whole life belongs to the water. Everything about me is governed by the water. My priestess name, Omik Bemi, means the water carries me or the water supports me.

Omi: And it is, it has just been so, it has been so even beautiful, like, getting snowed the rivers of this place. Getting to know, I can't remember the indigenous name of the St. Lawrence River right now, but I was visiting the St. Lawrence River the other day and the St. Lawrence River was like, you need to come visit me more often, like where have you been?

Omi: Like, um, and, and that is really enriching. When I think about, you know, when I try to, when I try to communicate what it is that the water gives us, I think about Yemoja and Her name being Yaye Omoedja, which means Mother of the Fishes, a mother whose children are as plentiful as fish, and she is so, her love.

Omi: is charming, it's sensual, it is beautiful, it is poetic, and it is also violent. And it is also, you know, like, and I think that's like the duality of water. In our tradition, we say water has no enemies. That's because water, that's your friend today. may not be your friend tomorrow. Like the water that nourishes you today can also be the same water that causes a great flood as we see in a lot of different traditions around the world that talk about this great flood that happened.

Omi: I don't know when that great flood happened, but that also is something that is documented in Ifa as well. And I'm trying to think, what else would I say? I feel like I have so much to say, like, um, about the water. It's been, like, so long, this, like, just being with the water and sitting with it, and having it change me.

Omi: Let me

Amy: ask you for some advice, then, on behalf of our Coven mates, who, as I said, we've been talking more and more and more about water. How would you tell them to connect with water.

Omi: Oh my gosh. Okay. The very first thing, drink your water. Do not be dehydrated. I also need to take that advice. Drink some water, um, to connect with water.

Omi: I think also find your closest waterway, your closest water body and go there and spend some time and just bring offerings. Do not ever forget an offering water spirits. They are very like in Jamaica, we have this, this state, this word like stush, which means they're quite like. They're a bit like, I don't know what, what words to describe them, but they're like, um, you came here, you didn't bring an offering.

Omi: Why would you want something from me if you didn't bring something? So, highly, highly recommend you doing that, bringing an offering. The river that I go to has sometimes been like, I don't have anything to say to you until you give me an offering right now. Um, And so, so go there and spend some time and also cry there.

Omi: Talk to the river, like actually tell them, introduce yourself. Hi, my name is, this is where I'm come from. This is my story. Like, this is what happened to me today. This is why I'm here. This is why I'm showing up. Today like this is what I want from you because they also recognize that human beings want things.

Omi: This is what I want from you and I'm also prepared to reciprocate that relationship. We have to have, we have to be in a reciprocating relationship with our waters, with the land, with the earth. Um, Yeah, and not be afraid to go at night either. Sometimes I've been afraid myself to go at night because it can be a little scary.

Omi: But the water at night, it can be so like you can see even a different side of yourself. Like when you're staring into black water, like it can be so It can just, I'm like, like reflecting on my own experiences going to the river at night and just how sacred that aloneness can feel and to have and to be witnessed and embraced by something that is so like other than human, like, but still recognizes your humanity and still recognizes that, you know, like how much you change and grow and also wants to see you change and grow as well.

Amy: That was so beautiful. That's perfect advice. And also, don't ever come empty handed, no matter where you're going. But let's turn away from the beauty and dive into human ugliness for a minute. I want to know, how, did witch trials impact the practice of spirituality and the, Iyami in Black, Afro descended communities in the diaspora, and what was the role of patriarchy in all this, by your view?

Omi: You know, it's so interesting. I was doing, I was doing some research on when the witch trials really started, and I think I, I think I just, sometimes I hear the message on the wind, and it's like, aren't you curious about the witch trials? Like, you need to learn a little bit more. about what really happened in Europe and because of course they started in Europe and they made their way over to the Americas through, I think, Pilgrims.

Omi: I could be wrong on that but, um, I think the witch trial started in the early 1400s and of course we learned that it was women, primarily women, not exclusively women, Who were, you know, healers, midwives, seers, women who were actively involved and engaged in the care of their communities outside of the power of the church or in a realm where the church had little to no like effective power.

Omi: And we see as the church is starting to really. Go through its further transformations to be in service to empire that we see these women start to be targeted and they are usually by men with Bibles, which is no surprise, like men with Bibles who are Accusing them of usually, you know, this, the typical stuff that they accuse, which is, uh, which is like eating children or killing, killing cows or anything that is like, you know, illegal, according to that one Bible verse, which I can't remember, but that says like, you must not suffer a witch to live.

Omi: Um, and so that we see that happening in the witch trials. And then I think around 90 years later, when Columbus first set sail and Europeans start to make their way down into the African continent, a lot of the rationale that was used to kill and hunt, which is, was the exact same rationale that they used to destroy our, our West African, like spiritual traditions, spiritual traditions.

Omi: For example, actually the army, no one could become King. Or it could become chief or Oba without the approval of the army. So in a sense, they're also King makers. So they will usually watch someone be like, okay, this person has the, has the good character has good Iwa, Iwa Pele, and they're sufficient to lead.

Omi: And so there was a resentment there, I think from, from men around how it is that, you know, they have to kind of ask for their power. Their power has to be handed to them from our mothers. And. They use that rationale that patriarchal rationale, um, to suppress the AMI. And then from there, once colonialism really started is that we see like in our communities, like even knowledge around the AMI starts to become suppressed.

Omi: And. And even spirituality itself becoming suppressed as was something that happened a lot like in the Caribbean and in the Americas with people not being allowed to practice their indigenous spiritualities. And even in Jamaica to this day, there's still a law on the books that you are not allowed to practice Obia, which is what it's called in Jamaica.

Omi: You're not allowed to practice Obia to this day. And it can still be punished. And I also want to shout out. That yesterday, my olori, she told me about a story in Haiti where I think two days ago over 100 Haitian voodoo elders were actually murdered. Um, like, like all people, like 80, 80 plus, like elders were murdered.

Omi: And the story, the story for that just reminds me of how much it is. Considered dangerous, I think, and it's still dangerous to the structure, the power, the existing power structure, um, to be connected to the earth. And that's also what this is about, right? Like, this is about your connection to the earth, defending the earth, protecting the earth in a legacy of, I think, capitalism, where there's like an endless drive for production and innovation that doesn't take into account.

Omi: You know, the earth and like being in sacred relation with the water, with the fishes, with the trees, with the sun, um, and not just taking, taking, taking, taking, taking. And so, yeah, like I would say, like, those are the similarities, I think, that I found really striking when I was doing this research. I was like, oh my gosh, like, this sounds so familiar to the narratives that I heard growing up about witchcraft and witches from my evangelical parents.

Amy: Melissa just dropped into the chat, um, to ask for book recommendations. I'll give you a second to think while I tell you, Melissa, that I always recommend Ona Agbani by Eyalosha Akalatunde. She's been on the show a couple times. She's got to be Oshun on Instagram, one of my favorite authors on the subject, but I want to hand it to Omi now for your, for your recommendations.

Omi: Oh, thank you. I didn't know about this book, so thank you for those recommendations as well. I am currently reading, um, Mami Wata by Mama Zogbe, who is a now deceased Mami Wata priest. When it comes to, like, I think that really gives you a great reference of knowledge that even precedes Esheshe. Um, it's quite ancient.

Omi: She did a lot of amazing research in that book. And honestly, a lot of these things are things that I know from sitting before my shrines. Um, so I wish I had more book recommendations, but that's the major one that I would, that I would share with you.

Amy: Um, can you tell me again, Mami Wata? Can you spell that for me?

Omi: I can, I'll type it in the chat, but I'll also find the book link. And send it because there's like a, it's like a longer title, but I can't remember what the rest of it is.

Amy: Listeners, it's M A M I W A T A and Omi's gonna send me the link and I will put it in the show notes for this episode in case you're curious.

Amy: I know I'm putting it on my TBR immediately. And before we wrap As much as I hate to conclude this conversation, one that I hope will be just the first of many. Again, Omi is local, so watch out on Instagram, you may see our faces smashed together in a selfie in the coming months. But before today, like in a previous conversation, um, you mentioned that the Iyami, that feminine power, is going to return as a global governing power.

Amy: And I just like, it makes me feel good in my body to even just hear those words. So please expand, please, please tell us about this like, global governing power returning to like, a femininity.

Omi: Oh my god, I love the way you speak. I'm like, yeah, I guess I did say that, didn't I? Oh, um, when I I think as many of us can see, you know, sometimes it's about putting the pieces together.

Omi: We're seeing a lot of women, first of all, like returning to these ancient traditions. Maybe, you know, and in a way, they always kind of stay with us. At some points, they may just be in the background. Oh, you don't know why your mom is like talking to that picture of your mom or of your grandmother, or you don't know like why, you know, they're like all these all the different types of rituals that I think surround us.

Omi: And we're seeing a lot more women start to pursue them with a bit more intention. And I think that is one part of the call of the mother. And one of the things that I wanted to say too, is that the Eami are present, not just in Asheshe, they're present as Inanna, they're present as Ishtar, they're present as Astarte, they're present as Kali, they're present as Freya, they're present as Brigid, like this is really like a global power, like that is not just located to any specific place.

Omi: And so, You know, in my own tradition, this year was marked as actually a very major year for the EME and very much a major year for women and for women to start speaking up more and to start, um, like, being respected also by men because, like, basically the Odoo suggests that, you know, men basically, like, There's not much further that you can take this, it is women that can actually elevate the nation, or elevate the community, economically, sociopolitically, in all these different senses, and so, you know, I've seen some people point to, like, cases of high profile celebrities who have, you know, abused women and children, who are now, like, also going through their own accountability process, and sometimes maybe that accountability process is jail, you know?

Omi: Might be death. Like it could be like a lot of different things. And so we like this is how it kind of starts in our tradition. We it is noted in Odoo Osagunda that there will come a time where this endless progress this endless creation cannot continue. Which is kind of where we're at right now, like, and we will have to get back into sacred relationship with the earth, with the water, with everything around us and to not see ourselves as, you know, I think from the enlightenment period, which really like props up the human being, especially with the man as being like the God and anything that he wants to do.

Omi: There's like the world is his oyster. Is that, that. That is not sustainable. And so we have to return to this tradition. And I think any earth based tradition is ultimately about the mother, like the mother earth, you know, like this is our source. This is from which and from where we come. And so I'm excited.

Omi: I'm super excited about this, about this governing power. I'm super excited to see the EME come back, not as like, uh, you know, the second coming of Christ, but also in, you know, in our relationships, in me and you, like in the people listening to this, to this podcast, the people who will become leaders in their community.

Omi: Who will hold that sacred matriarchal maternal power, you know, it's the YAMI is also in all of us. That's something that I wanted to say that I didn't say before the YAMI is in all of us. Anyone who has a womb, you are already connected to that power. The power associated with creation of birth. You know, in my tradition, that's one of the reasons why it's extremely important to respect women and to respect elder women, especially because of the power that is in their body.

Omi: And so, also, maybe I want to be specific that it's not just cis women who, you know, have access to this power. Anyone who has a womb has access to this power.

Amy: And we can think of a womb as being metaphorical and not just like a literal uterus, right?

Omi: Precisely, precisely. I think a whole other thing around like trans, transness too, I feel like, you know, sometimes there is this idea that like, oh, like, I've seen people who are, who are in a chaché say, oh, like, you have to be a biological woman to be a connect, to be connected to the immune.

Omi: It's actually not true. Like, it's simply false. Like, and even this idea of like a biological woman, it's like, what do you mean by that? Because also in our tradition, you know, initially talks about some people like in their past life, they may have been like a cis woman, for example, and they come back and they're not a cis woman, but they might still be very connected to that past life.

Omi: And they should be left alone to like, live out like whatever their ori, their spiritual head, like says that they should live out as. And so I think that further, I think, gives credence to this idea of like, why Esese could never be transphobic. Because if you really if you really studied. Like, it's just not true.

Amy: And we, we have so much, like, so many ancient deities are genderless, or gender non conforming, or gender swapping, I feel like, um, I heard, and maybe, maybe it was, uh, Maybe it was Eolosha who even said, like, and if it wasn't her, it was someone equally as brilliant who referred to Jesus as like, a Johnny completely deity, like a new deity, and I was like, yeah, you know, like, 2000 years is not that much time, you know, we have 70, 000, evidence of 70, 000 year old snake rituals, you know, like, There is, it's, the universe and divinity is so much more expansive than the patriarchy would have us believe, right?

Omi: 100 percent and I love that you brought up snakes because snakes are also connected to the water and what I was saying to you earlier about Mami Wata and Yemoja and Oloku and also they're all connected to the snakes like the water is literally where our our brilliance And even Olokun is, you know, there's parts of Olokun where Olokun is genderless, where Olokun is a man, where Olokun is a woman, where Olokun actually has both, like, sex organs.

Omi: Like it's, it's, it's just, it's in us. It's really, really in us.

Amy: Thank you so much for sitting down with me. I am absolutely vibrating. I'm so excited to share this conversation with the Missing Witches Coven, and if they want to follow you, which I know they will after listening to this, um, what's your Instagram handle?

Amy: What's the best way to support you? What, what's your ish?

Omi: Oh, okay. My Instagram is blue semiotics. So, B L U E S E M I O T I C S, I'm obsessed with the colour blue, that is Yamoja's colour. And, that's, that's, I think that's the best way to reach me, that's the best way to reach me.

Amy: Thank you again so much.

Amy: Obviously, listeners, I will put, um, Omi's Instagram handle in the show notes for this episode, if you, uh, don't have a little pen and paper with you, as you're listening to this, wherever you are. Again, I just want to thank you so much, Omi, for reaching out. Um, Jennifer's in the chat saying she is literally following you on Instagram right now.

Amy: Let's We are all going to stay connected. And again, I really hope that this is just the first of many conversations. Thank you again for reaching out. Um, you know, normally I have like a whole process of vetting and research, and I got your message and I was like, I want to talk to this person. I want to meet this person.

Amy: I'm so excited about what this person has to say. And you are even more enthralling and wonderful than I am. had in my imagination. So again, thank you so much for being with me, for reaching out, just for being like super rad and amazing. Do you have any parting words for the Missing Witches Coven, before we click, click out of here?

Omi: Oh my god, thank you so much for those really kind, those really kind words. I'm so grateful and I'm so grateful that you answered my message. It was kind of a shot in the dark. I was like, Hey, like I'm a fan of this podcast. I would love to get to know more people in the Montreal area who know the mother like in a very intimate way.

Omi: And I feel very lucky. I mean, I feel like I was told to do that actually. And I'm, I'm very grateful to have been here to have even like seen some of your faces, the people who were here in the zoom room. And I'm really excited to get to know like your work more and to get to really like, yeah, hopefully this is just the first of many conversations.

Omi: And I'm looking forward to, you know, contributing further to supporting, to being present, to just being around. I'm, I'm really like, my heart is like very warm and thank you for receiving not just me but my Arisha, for the mother, for receiving the Iyami in this way because I'm in, I'm in this room with five shrines right now.

Amy: You definitely did not come to this conversation empty handed. You brought me so, so, so very much. And again, I'm super grateful. Thank you so much. And, uh, blessed fucking be!

Omi: Blessed be! Blessed be!