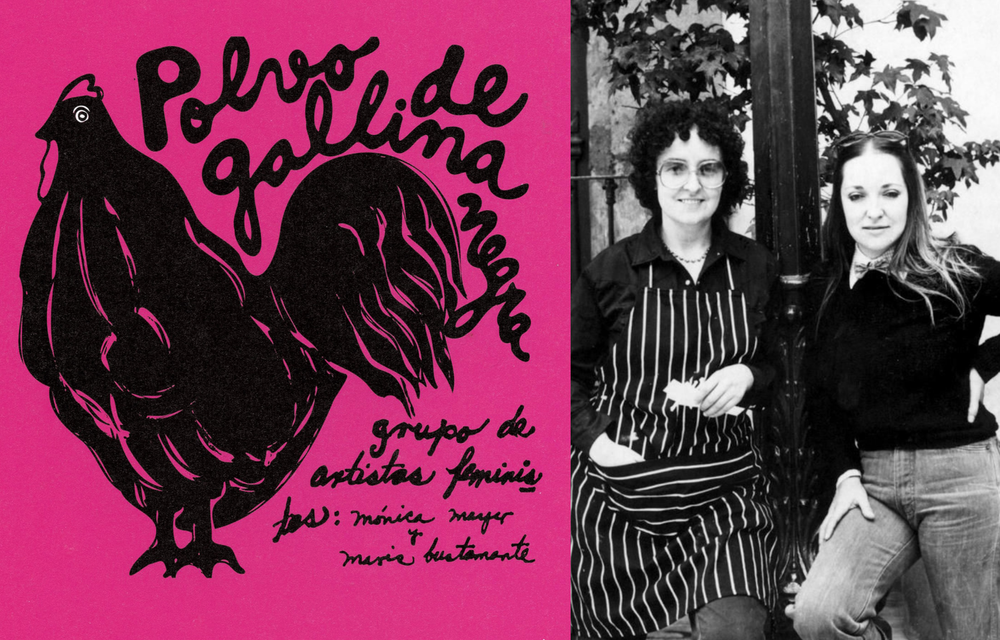

Today, Amy is adding Black Hen Powder, Polvo de Gallina Negra, to our shared apothecary, to our botanica of story spells we can conjure when we need a boost of magical, creative inspiration. We offer up Polvo de Gallina Negra (Mónica Mayer and Maris Bustamante), a feminist art collective from 1980s Mexico, sometimes hailed as the first feminist art group in Mexico, who used magic, laughter, intellect and art to change the world.

I like to include the story of a collective in each of the fall seasons of the Missing Witches podcast. So far I’ve written about WITCH (women’s international terrorist conspiracy from hell), and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence… as a reminder - amid stories of the power that an individual person wields, singular stories that I hope will inspire and empower you, dear Coven, to know that your actions have the ability to change the world, to be set down in history - that some of our greatest accomplishments must be made when instead of working alone, we work together. I like to include stories of collectives to encourage us all to collaborate, find like-minded Witches with common goals to help us reach beyond what we can do on our own, to break down the lie of individualism, and include as our role models Witches who work together.

Today, I’m adding Black Hen Powder, Polvo de Gallina Negra, to our shared apothecary, to our botanica of story spells we can conjure when we need a boost of magical, creative inspiration. I offer up Polvo de Gallina Negra, a feminist art collective from 1980s Mexico, sometimes hailed as the first feminist art group in Mexico, who used magic, laughter, intellect and art to change the world.

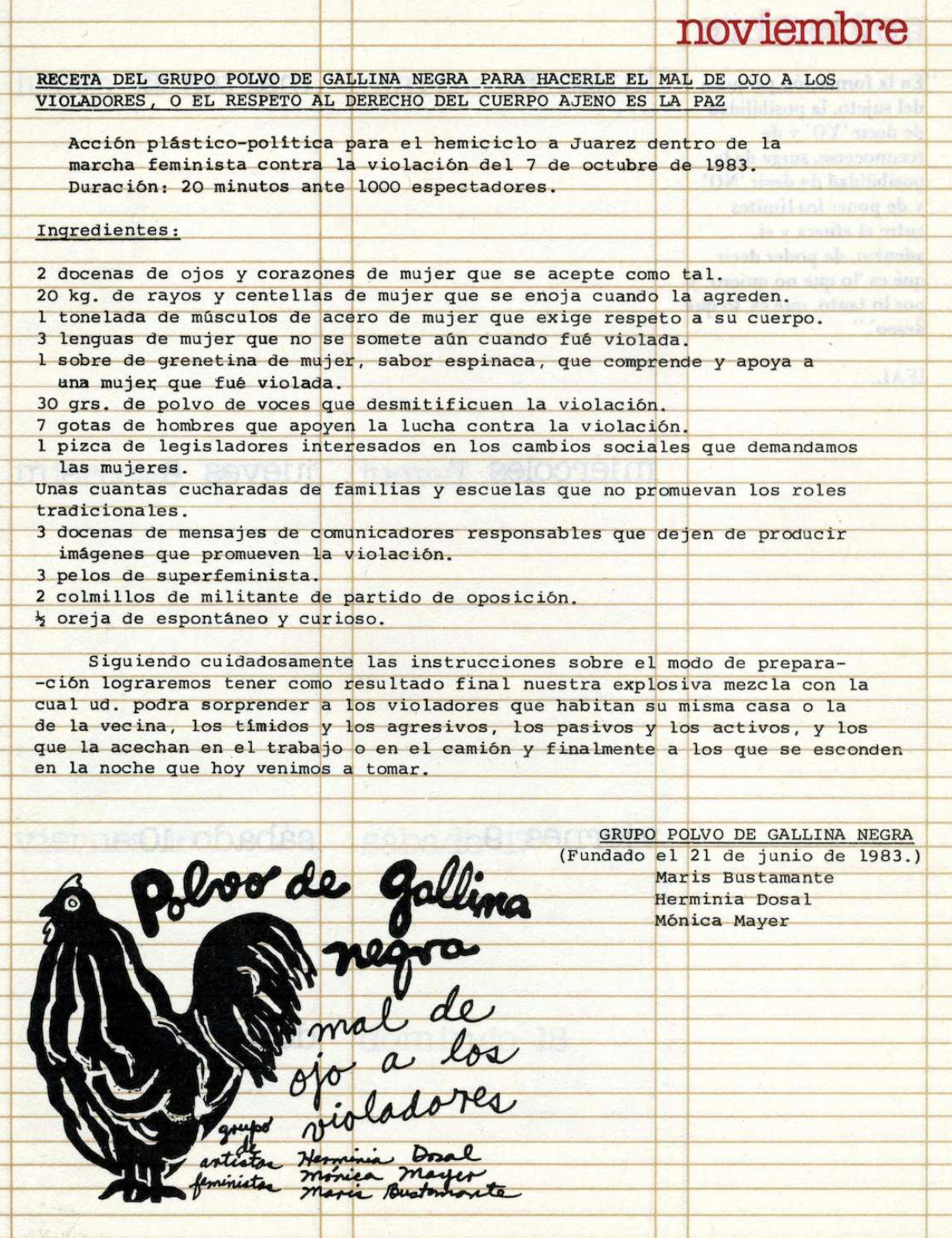

In 1983, in the streets of Mexico City, two witches whose craft was forged in the kiln of art and resistance, and honed on an anvil of humour and politics, or perhaps due to their focus on domestic labour, I should say, baked in the oven and smoothed on the ironing board…Mónica Mayer and Maris Bustamante, cast a feminist spell. Their chosen magic was social subversion through performance, using art as a tool to hex the patriarchy. Named after a Mexican folk remedy to ward off evil, Polvo de Gallina Negra made art with the same intention: to protect, to awaken, to empower and enact the ancient alchemy of rebellion.

The Witchcraft of Protection takes many forms.

“The name Polvo de Gallina Negra translates to “black hen powder”, a traditional remedy used as protection against the evil eye, which [Mónica and Maris] anticipated they would receive in relation to the feminist content of their work. The group outlined three key goals they wished to achieve: “(1) To analyze women’s images in art and in the media, (2) to study and to promote the participation of women in art, and (3) to create images based on our experience as women in a patriarchal system, with a feminist perspective and with the goal of transforming the visual world in order to alter reality.”

Black Hen Powder, a folk magic tool with origins in Mexican brujería and Southern hoodoo traditions, is typically used for protection, cleansing, and reversing negativity. It is named for its association with black hens, egg-laying creatures often regarded in magical practices as symbols of defense and transformative energy. And Polvo became this magic personified.

Protection Magic takes on many forms - sometimes it’s the blocking of the evil eye, deflecting negativity, sometimes it’s a call to arms, sometimes a bowl of soup that tastes of a mother’s love.

Monica said “Our art isn’t separate from life. It’s a form of activism, a way to raise consciousness and bring about social change.”

Dorota Bizcel wrote, “Building on tactics developed by social movements, PdGN sought to reach mass audiences through the deployment of mail art, performances in urban spaces and public institutions, and participation in communications media, always with sardonic humor. They inserted themselves into street demonstrations protesting violence against women (1983) and against the tightening of abortion laws in Mexico (1991). In 1984, wearing distinctive boots and aprons covering their visibly advanced pregnancies, Bustamante and Mayer gave more than thirty performative lectures on women artists. From 1984 to 1990—in museums, at universities, and on television— they debated and questioned stereotypes surrounding motherhood.”

In Drawing Down The Moon, Margot Adler wrote “A group of women in a feminist Witchcraft coven once told me that, to them, spiritual meant, “the power within oneself to create artistically and change one’s life.” Risa and I have often defined Witchcraft as that point of intersection between our spirituality, our politics and our creativity. We Witches recognize the creative impulse as something we have in common with our Creator - a divinity that invents, designs and constructs a world in which we want to live.

Maris said “Motherhood is a political act, an act of creation, but also one of repression if seen through the lens of patriarchy. We wanted to disrupt that narrative.”

Monica wrote: “one day, in the early seventies, during a seminar at art school at the National

School of Art (alias "San Carlos") where I was studying, a fellow student gave a lecture

on women artists and to my surprise, at the end of her presentation most of the

(male) students agreed that it was because of our biology, we could never be as good

artists as them: motherhood took up all of our creativity. Apart from the

astonishment I felt that they accepted this highly unscientific concept, particularly

as they were artists and intellectuals and therefore generally considered to be

progressive, that discussion made me understand that as an artist not only would I

have to face such misogynist crap, but that it was up to me to try to do something

about it. I understood that even if I produced the best artistic work in the world, the

fact that I was a woman would affect the way in which it was received negatively.

For the first time I was saddened by the enormous artistic potential humanity had

wasted as a result of these stupid prejudices.”

Even their own pregnancies were re-contextualized as part of Polvo’s artistic output. To work on a project about motherhood, the two suggest, the first step was to both get pregnant at the same time. Maris said, “We were so scientific about this, and our methodology was so perfect that [Monica’s] daughter is only four months older than mine. Can you imagine the precision of our methodology?! How scientific our group is!”

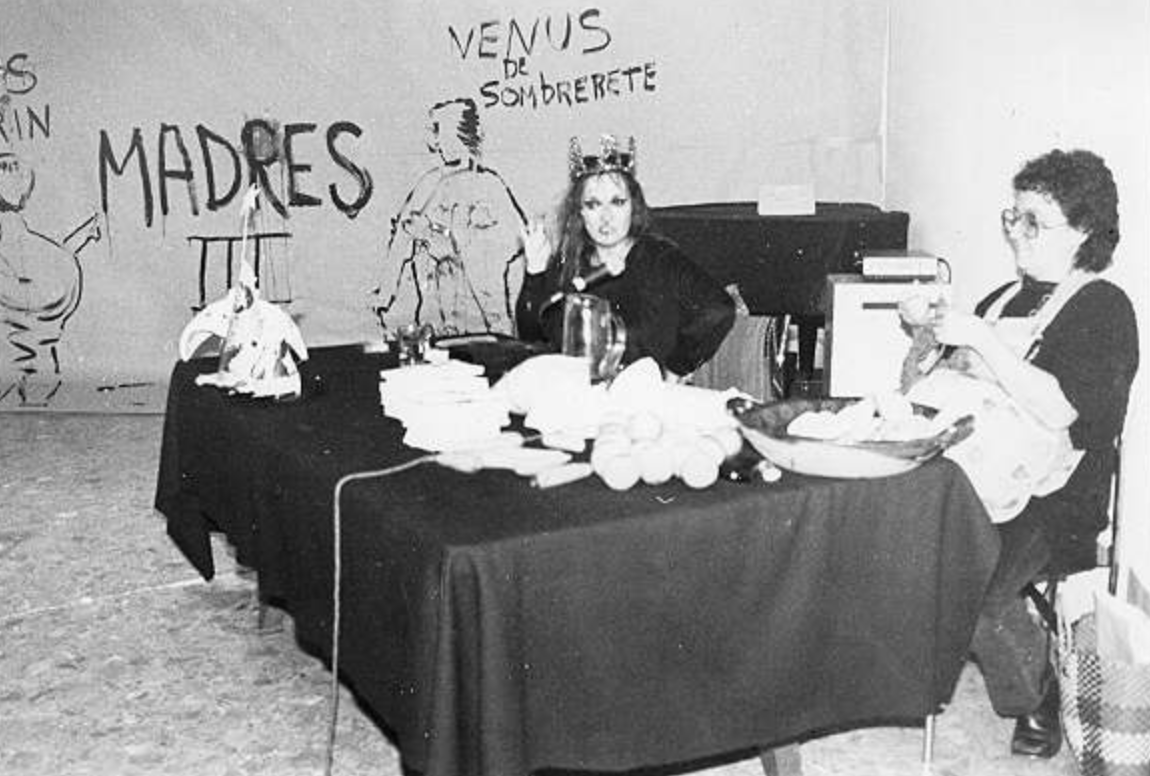

1983’s “Madres,” (Mothers) which began on May 10th, Mother’s Day in Mexico and continued for many months, challenged traditional representations of motherhood in Mexican society. The performance critiqued the idealization of women as only mothers, exposing the contradictions and pressures placed on women in patriarchal culture. “Madres” shattered the idyllic image of motherhood, reclaiming it from the confines of patriarchy. They showed us that being a mother is both sacred and political, a radical act of creation, but also a space where women’s bodies are too often both vulnerable and controlled. Polvo exposed these contradictions, turning them into a pop culture visual language they hoped would be impossible to ignore.

“We believe,” said Maris, “a new image of women in the media, in art and performance is feasible.” Monica adds, “Most images of motherhood have been painted by men [...] women’s experience has not been portrayed. This may be why there are very few paintings of mothers and daughters.”

Madres was a multifaceted intervention addressing the theme of motherhood, blending humor with feminist critique. The project included several performances and social experiments designed to challenge traditional gender roles and the cultural expectations placed on women - especially mothers.

Poignant but playful, Monica once quipped, “Oops, the baby woke up; I will have to fix the world another time.”

Madres included the Letter to my Mother contest in which the public was invited to participate by writing a letter - everything they didn’t our couldn’t say to their own mother - to be used in a gallery show. They sent collages with texts and images to 300 critics, artists and journalists with the title "Egalité, Liberté, Maternité: Polvo de Gallina Negra attacks again".

In an interview you can watch on YouTube, Mónica and Maris appeared on the Mexican talk show Nuestro Mundo where they performed what they called a ritual.

This appearance was also part of the larger project of Madres. Maris and Monica persuaded the host, Guillermo Ochoa, to dress as a pregnant woman in a segment titled "Mother for a Day." He wore a foam belly and yellow apron, and was crowned “queen of the home,” while the studio audience laughed along. Maris tied the apron strings behind Guillermo’s back and declared, “now you can feel the evil eye. You are starting to need your Black Hen’s Dust.”

Maris places a golden pipe cleaner crown on the host’s head. They present him, ritualistically, with tiny objects - a pill for cravings, a coin for luck, pasta for the expectation that he should cook. Confused, Guillermo interrupts with bad jokes to diffuse his growing discomfort.

This performance attempted to shift the notion and experience of pregnancy and domestic labor out of the home and on to television, into the public sphere, and suggested that anyone could inhabit the role of a mother, questioning the biological essentialism surrounding the idea of motherhood.

Maris wrote “[W]e grew while we built our families, so we had a lots of fun discovering that the social and cultural reality is penetrable.”

To use a phrase that predates photoshop and deep fakes: Seeing is believing. So what happens when we extend this idea into our witchy creative arts? When we make something, when we change something, we are in fact changing the world. Changing what we believe. Something that did not exist, now exists.

I think of that old movie trope where simply by removing one’s glasses, an ugly duckling is transformed into a prom queen. So much of our identities are based on a visual presentation - our hair cuts, how we decorate our homes, the clothes we wear - so much of our consumption is based solely on the image we want to portray. Everything we see, from the architecture of cathedrals to Angelene on a billboard - even gender - is a form of visual language, a mode of communication where we tell the world, as individuals and as a society, who we are, and what we believe. Tweaking our appearance can completely change the way the world sees us. Even our facial expressions and body language are forms of cultural communication that can be changed on a whim. (Side note: I wish all of you could have seen my face when I discovered the existence of Polvo, aglow and agape as I learned about their work and the thought and intentions behind it - my face might be better at conveying my excitement than my words - the goal of transforming the visual world in order to alter reality...)

So if changing your appearance alters your reality, not who you are, but how you’re treated, how the world perceives you, then changing the appearance of the world might just affect how we perceive it, how we treat each other.

This is why representation matters. Because what we see can affect how we think, how we feel about ourselves, how we go out into the world.

When it comes to Art, seeing a work can change how we see the world. Transforming the visual world alters reality. Cultural reality is penetrable.

They said:

“We don’t just denounce machismo; we laugh in its face. To confront a system this ingrained in society, we must subvert it from within, with our voices, bodies, and art.”

“We decided to work with humor because it is an effective weapon. Humor can destabilize and disarm oppressive structures while making serious points.”

“Humor allows me to move in spaces where seriousness limits freedom”

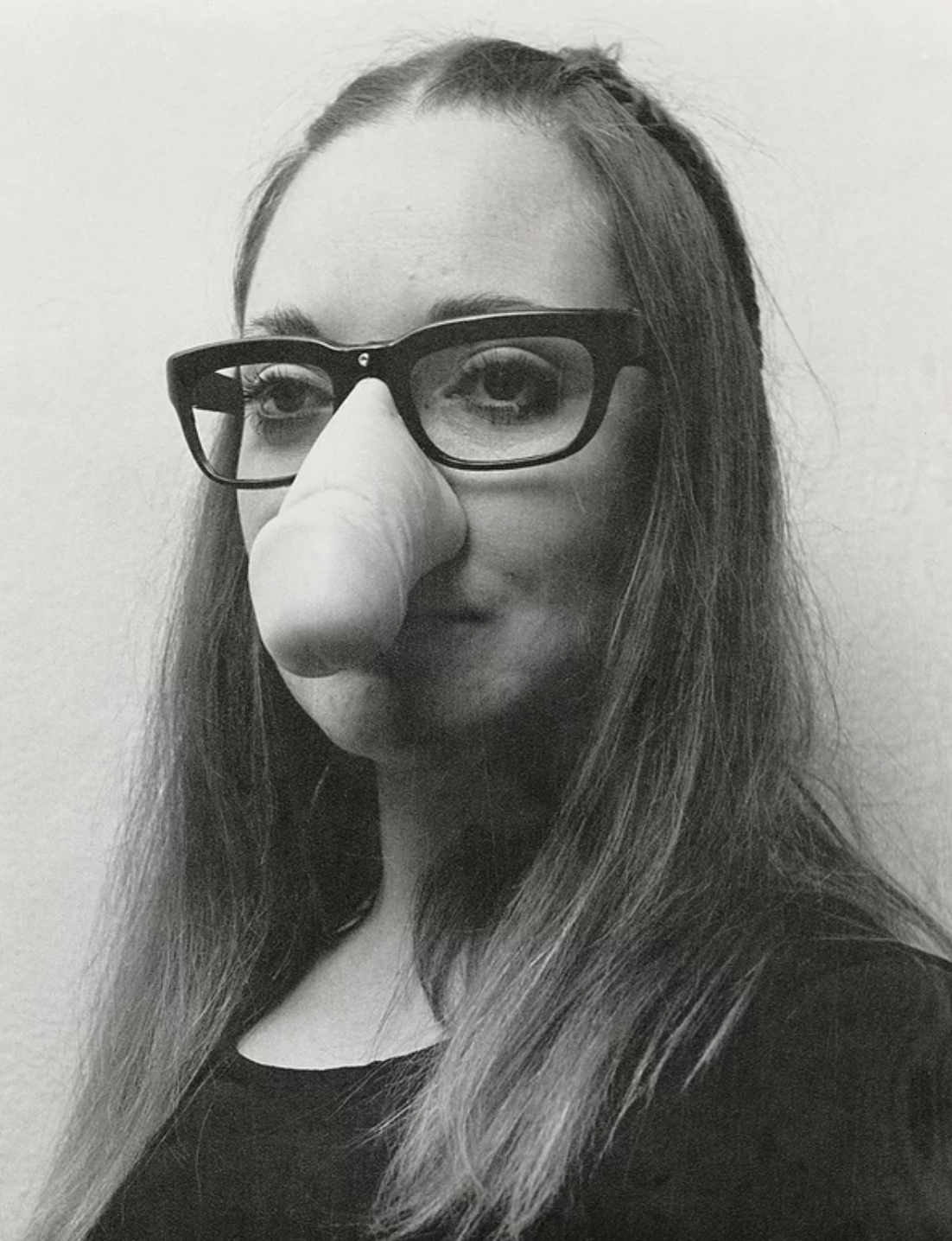

In 1982, before the collective creation of Polvo, Maris made her work El pene como instrumento de trabajo/ Para quitarle a Freud lo macho (The penis as a work instrument /To get rid of the macho in Freud), 1982. It’s a series of photographed self-portraits where Maris wears a Groucho Marx style fake nose and glasses, but the nose is a girthy penis.

She said “Sexuality and gender in art should be free from the limitations of culture’s definitions.” Her groundbreaking “El pene como instrumento de trabajo” ("The Penis as a Work Instrument"), critiqued patriarchal perspectives, particularly those of Freud, by using humor and satire as a method of subversion.

Humour in political art is a spell, a conjuring force. It disarms, it destabilizes, and it sneaks critical ideas into spaces that might otherwise remain hostile to change. Humor is the witch’s sly grin, knowing that laughter loosens the knots that bind us to oppressive systems. Political artists like Polvo turned humor into a weapon of feminist resistance, using satire to pierce the heart of machismo and authoritarianism. Polvo used absurdity to unravel the patriarchy’s obsession with power, reducing the phallus—a symbol of dominance—to a prop of ridicule.

Humour in political art also creates a bridge between the personal and the collective, inviting our participation in the act of rebellion. It allows people to laugh at their oppressors, a laughter that is inherently revolutionary. Dadaists and Surrealists recognized this power during times of crisis, where humor became a response to the horrors of war and totalitarianism.

Laughter shifts perspectives and challenges entrenched beliefs not by direct confrontation but by reframing the narrative through irony, exaggeration, and absurdity. I took a friend to see Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with me, a midnight screening of a cult film by David Lynch that at the time had been haunting my nightmares for 20 years. My friend had never seen Twin Peaks and he laughed throughout. And somehow, because of his laughter, the film never scared me again. His laughter had reframed the whole experience and cured me of my fear.

In a playful resistance, humour becomes more than an escape; it is a tool of awakening. Laughter cracks the facade of authoritarian control, planting seeds of dissent in fertile ground. It’s an incantation for survival, for reclaiming spaces where we can breathe, create, and ultimately, resist.

And I think of that scene from the Witches of Eastwick where the three main characters discover that laughing gives them the power of flight.

Monica wrote: “I think the most important thing feminist art has given me is the understanding that an artist’s work is more than producing art works. Doing research on women’s art, writing about them in my newspaper column in El Universal or publishing books about us, teaching, protesting and supporting other women artists is part of my work.

As time went by, the loud, obnoxious, radical feminist art movement I so much enjoyed became more institutional. I suppose it’s part of the process, and what allows archives such as this one to exist. Today, what we did is history. However, I also know that, at least in Mexico, there is a very strong new generation of women artists who will fight their own battles with as much enthusiasm as we did and hopefully, they will have as much fun.”

For the women’s march of early 2017, I had an idea. A big penis and testicles pinata with the words “Smash The Patriarchy” emblazoned on the long pink shaft. I had brought my father’s boxing gloves and invited protesters to punch the symbol of hegemonic machismo, urging them on, “don’t be afraid - when you smash the patriarchy, candy falls out.” Some students from McGill University were making a kind of documentary on the day and approached me for an impromptu interview. They asked why I had made the penis pinata. Truth is, I hadn’t really thought about it, I had just set about with my shredded newspaper, flour water paste and pink paint. I suppose that in the days leading up to the march, I had been more concerned with the How than the Why. “I’m so tired of being angry,” I told them. “I just wanted to have some fun.” That day, in Halloween style, I momentarily traded anger and fear for candy.

Throughout the 1980s, Polvo continued to expand its activities, conducting a series of public interventions and performances in Mexico City, their work confronting not only gender inequality but also related issues like reproductive rights, the undervaluing of feminized labor, and the objectification of women in mass media. In 1987: Creation of “Sin Título (Without Title)” Polvo de Gallina Negra created one of their most famous works, "Sin Título", which critiques representation of women in the media, using parodies of sexist advertising, disrupting the expected narratives around femininity. Created by Mónica, Maris, and photographer Herminia Dosal, featuring elements like handwritten letters, performance art documentation, photographs, sound and film.

At the core of "Sin Título" was Polvo's conceptual approach: combining personal narratives with public interventions to critique stereotypes around motherhood and femininity. Transforming the visual world to alter reality. The exhibit often incorporated audience participation - asking women to reflect on their experiences with gender violence. These statements were later displayed, bringing attention to the systemic injustices faced by women both in domestic and public spaces. This echoed Monica’s 1978 work "El Tendedero," which translates to 'the clothesline.' where she distributed pink postcards to women, and asked them to write on the cards, finishing the sentence, “"As a woman, what I hate most about the city is..." Monica took the responses, many of which reflected on the sexual harassment that women experienced at work, on public transportation and throughout their daily lives. She hung the cards on multiple clotheslines, conjuring both the domesticity and reality of women’s lives that Polvo would later cover in depth.

Also in 78, Monica made "Lo normal" a series of postcards in which she questions the established concept of normality through a playful survey on desire.

The feminist art group Bio-Arte was a collective that emerged from a Feminist Art Workshop taught by Mónica in 1982. The group’s work centered on the biological changes women experience. For this performance at a feminist art festival put on by Polvo, Bio-Arte crafted quinceañera dresses out of transparent and printed plastic, symbolically referencing the "packaging" used to represent young women’s entry into the marriage market. Quinceañera was a theme that came up a lot in Polvo’s work, and Bio-Arte aimed to provoke reflection on the ritual of quinceañera.

Polvo’s goals were “(1) To analyze women’s images in art and in the media, (2) to study and to promote the participation of women in art, and (3) to create images based on our experience as women in a patriarchal system, with a feminist perspective and with the goal of transforming the visual world in order to alter reality.” And they succeeded. Their magic dust worked.

Monica wrote: “for me the hardest feminist

struggle has been the one I fight against my own upbringing every day. Although I

have read thousands of pages on feminism, participated in tons of demonstrations,

worked in groups, organized exhibitions and written hundreds of articles, I must

admit that my heart was formed within the fierce machismo that surrounds us.

Changing these behaviour patterns so that my kids grow up with a different

experience, or so that my own expectations as a woman and an artist are different,

has been quite difficult. Having the enemy within oneself makes it hard to overcome

all the contradictions. This is why, when I think on how ambitious the feminist

project is (or the hundreds of feminist projects are), when I realize we are trying to

change the essence of society itself... I realize we still have a long long way to go.”

Polvo de Gallina Negra’s work will continue to inspire new generations of Witches and feminist artists on our long way to go. They broke ground, and the world looks different because of them.

In 2016, the (Women's Institute of Mexico City bestowed upon Monica the Omecíhuatl Medal for her "outstanding participation in education, arts, culture, and sports, which have inspired and impacted the development and empowerment of women".

By the mid-ninties, Polvo had disbanded, but left traces of their spells all over Mexico. Their Black Hen Powder filled the air and swept across the globe, covering us all in a thin layer of protective dust that is feminist art.

Because Mónica and Maris didn’t just make art; they conjured a movement, inscribed their magic into spaces where women’s voices had been demeaned and silenced for too long. Polvo de Gallina Negra were witches of the everyday, tackling the sacred within the mundane, their powder of protection sprinkled in corners of kitchens, city streets and art galleries, infusing spaces with a visual language of struggle and resilience. They hexed the old stories, confronting the violent machismo that permeated their society and laughing in its face, and wrote new stories, a quilt and collage of the stories they were missing. Their works were rituals of collective consciousness, and collective unconsciousness.

They taught us that we can transform the visual world and alter reality, that cultural reality is penetrable… So as we round out this season of the Missing Witches Podcast, remember dear Coven, that everything you do has the capacity to change your reality, or someone else’s. Your art is not separate from your life. The Witchcraft of Protection takes many forms.

Our magic dusts are working.