In today's episode, Amy fosters her friendship, and hopefully yours too, with poet Mary Oliver, who's work is a love letter to nature, and to noticing. But Amy discovers that the real Mary was not exactly who we assume her to be.

LISTEN NOW, TRANSCRIPT BELOW

Transcript:

You Are Standing at the Edge of the Woods by Mary Oliver

[...]

The moon,

in its shining white blouse,

rises.

And whatever that wild cry was

it will always remain a mystery

you have to go home now and live with,

sometimes with the ease of music, and sometimes in silence,

for the rest of your life.

I know I will read Mary Oliver’s poems, sometimes with the ease of music, and sometimes in silence, for the rest of my life.

This season marks the five year anniversary of the Missing Witches Project. Missing Witches has led Risa and me to discover, meet, learn from, and fall in love with so many witches, past present and future. Some we met in books, some on Zoom, some in person with hugs and food and deep conversation. Marija Gimbutas led me to Starr Goode, Zora Neale Hurston turned me onto Faith Ringgold… we follow breadcrumbs to gingerbread witch houses in the woods and take tastes of sweet foundations.

But never before have I felt as if a spirit didn’t simply want me to learn about them, didn’t simply leave subtle hints around for me to find - but rather, in the case of Mary Oliver, she positively demanded to be included and take her place in the Missing Witches pantheon of ancestors, aunties and guides.

Mary seemingly insisted that I learn about her, read her poetry, and share what I found with this Coven. See, there was a period where, in my life anyway, she was inescapable - around every corner, her poetry memed into an algorithm that seemed DIVINELY designed to infiltrate my psyche and not let up. Everywhere. Again and again. Every google search result for poems about blank somehow alluded to her work. At a certain point I said aloud, “Ok Mary I see you, I’ll learn about you. I’m noticing you.”

I gave Mary what she wanted: my full and explicit attention.

And then, in my research, and pouring through her poems, I discovered that noticing, that attention was the currency that Mary valued most. Not for herself. She was known to be a recluse, rarely gave interviews nor discussed details of her past.

No, Mary didn’t value being noticed, she valued noticing.

In her essay, On the Overlooked Eroticism of Mary Oliver, Jeanna Kadlac describes Mary as “a poet of attention.”

But I suppose in Death, Mary relaxed her reclusiveness, because as I told you, she told me to pay attention. Not just to our surrounding nature, our human nature, but to her. “Look at me! Pay attention to me” her presence nearly screamed in my ear.

And much like the woods or the beach, or a poem, the more attention I gave, the more my attention became appreciation, admiration that turned to wonder and adoration. I discovered details about Mary that I would otherwise have missed, and she went from a poet whose poetry I liked, to a dear friend, whom I love, to whom I turn with a wink and a smile, for counsel, for beauty. To get saved.

As I was writing this episode, an unwitting covenmate posted a Mary Oliver poem in our coven circle feed. I asked if she wanted to say anything about Mary for this piece. Blessed fucking be her heart, she sent me an essay. This is the effect that getting to know Mary Oliver has on us all. Asked for words, we deliver multiple glorious paragraphs of appreciation.

Mary sometimes makes you love her but always makes you want to write and write and write!! Our covenmate Erin Bensinger wrote:

“I consider Mary’s poetry a sacred text in my agnostic atheist pagan practice. Like her, I walk an earth-honoring path on lands where I am a multi-generational descendent of settler-colonizers. How do I reckon with my people’s bloody history on this land? How can I love it so while also being honest about the damage that has been done? I have come to believe, through her work, that the lifelong work toward creating the answers begins with listening and paying devoted attention.

Mary excels at capturing the magic in the mundane. In her work, every being is worthy of equal attention, and is an equal contributor to the whole of the messy, beautiful ecosystem. A blade of grass calls for no less attentive care than a fox, a carcass no less important than a butterfly.

As a character in her own work, Mary does not aspire to achievement. She is a writer, yes, but she comes to the craft with an attitude of collaboration. She is in constant conversation with the mystery of poetry, but still she keeps at her craft, shaping it along the way into what her desires deem it ought to be.

She reckons in a similar way with the Christian god. She frequently invokes the name of god and its associated motifs: prayer, repent, divinity. It becomes clear in her work, especially toward the end of her life, that the god she speaks of is not a patriarch in a throne atop an airy paradise. God is being, is everything, especially the tiny details, especially the bigger picture.

Her work holds dear some of my personal truest values: care, attention, animal companionship, land and life stewardship, death as a sacred rite, life as a beautiful mystery, and the written word as a powerful tool to convey it all. She sings loudly the praises of life’s natural glory, that others may too turn their senses to the world around them and listen. A quiet, natural evangelism. May we all be so.”

Thanks Erin.

Before I knew her, I had always imagined Mary as an angelic creature, wafting through the woods, pausing to notice the trill of a thrush, stopping and falling silent, weaving the pain of humanity into its song and producing, for us, a poem.

She told Steven Ratiner:

“I take walks. Walks work for me. I enter some arena that is neither conscious or unconscious. It's a joke here in town: I take a walk and I'm found standing still somewhere. This is not a walk to arrive; this is a walk that's part of a process.”

I imagined her soft, glowing, welcoming and unassuming. Above me. Above us all.

In Invitation she wrote:

just to be alive

on this fresh morning

in the broken world.

I beg of you,

do not walk by

without pausing

to attend to this

rather ridiculous performance.

It could mean something.

It could mean everything.

It could be what Rilke meant, when he wrote:

You must change your life.

Then I discovered a detail that brought Mary back to Earth, by my side, back down to the gutter and soil and ridiculousness where, frankly, I’ve always been most comfortable.

As I said, interviews with Mary are rare and few, so I turned to a video of her memorial, where people of note gave their eulogies. Maria Shriver, Hillary Clinton. And then the closer. Up to the mic crept The Pope of Trash and only in that moment did I learn that Mary Oliver and John Waters were lifelong friends.

Those of you who know me understand how important filmmaker John Waters is and was to me in my self-building. I became obsessed with his work when I was probably too young to be watching such scenes unfold. For better or worse, John Waters sculpted my young mind, molded me into a person who thought “freak” was a compliment, unafraid to take chances or make a fool of myself, I understood, as a developing child, that we must always keep our sense of humour, especially when we’re smashing the status quo. Be ridiculous.

In his eulogy, John Waters said, as if right to me, “Mary Oliver was not exactly who many of you think she was. She was no earth mother dancing through the woods in slow motion like a deodorant commercial. No, she could be a drama queen, she loved to feud - God knows she never suffered fools and was way beyond opinionated. I love that Mary, the contrary one, the angry but loving brainiac, the one that only nature could soothe… well sort of soothe.”

Worlds collided and I rethought everything. I noticed how much of Mary’s serene poetry was punctuated with roaring laughter. Learned how her long walks in the forest happened partly because she was so fucking poor that foraging in the woods became part of her survival. No woodland fairy, she was a puckish sprite - a chain-smoking lesbian who cursed and drank and was a trouble-maker.

Now, gracefully, Mary has relinquished her pedestal, and tumbled happily down to sit beside me on a bench and hold my hand, pointing out leaves and blades of grass and calling my attention to them. Mary and I are no longer creator and fangirl. We are friends.

Am I a fool to believe that from beyond the grave she wants, nay demands to be my companion on this noticing journey?

I find her reply in her poetry, A Thousand Mornings:

“Foolishness? No, It’s Not. Sometimes I spend all day trying to count the leaves on a single tree. To do this I have to climb branch by branch and write down the numbers in a little book. So I suppose, from their point of view, it’s reasonable that my friends say: what foolishness! She’s got her head in the clouds again. But it’s not. Of course I have to give up, but by then I’m half crazy with the wonder of it — the abundance of the leaves, the quietness of the branches, the hopelessness of my effort. And I am in that delicious and important place, roaring with laughter, full of earth-praise.”

I imagine Mary working as a secretary at ''Steepletop'', the estate of Edna St. Vincent Millay, and reading Edna’s poetry and studying it.

I imagine Mary’s bookshop in Provincetown, which she ran with her lover Molly. The two of them deciding to hire a young John Waters to work there and telling him he could have all the books he wanted, but he had to read them.

In her poem The Summer Day, Mary asked, "What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?"

So I’ll ask you all, dear coven: "What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?"

Mary’s early life was not easy. She said, “It was a very bad childhood — for everybody, every member of the household, not just myself, I think — and I escaped it, barely, with years of trouble. But I did find the entire world, in looking for something. But I got saved by poetry, and I got saved by the beauty of the world.” Mary was sexually abused as a child, and told interviewer Maria Shriver “I was very little. But I had recurring nightmares; there's damage. [...] that's why I wanted to be invisible, I'm sure. And it certainly made it hard to trust. But with the help of a few real good people, I finally feel healed—kind of late in life.”

What damage has made you want to be invisible, dear coven? I know, for me, solitude feels safe, and I sometimes have to force myself out of my hermitage. Because as much as interdependence may scare me, I need a community. We all do.

Mary described a certain witchcraft to podcaster Krista Tipett, saying poetry is “very sacred. It wishes for a community — it’s a community ritual, certainly. And that’s why, when you write a poem, you write it for anybody and everybody. And you have to be ready to do that out of your single self. It’s a giving. It’s always — it’s a gift. It’s a gift to yourself, but it’s a gift to anybody who has a hunger for it.”

I want us all to get into this ritual of writing. Just write. And write and write and write. For self, for community, a gift to give and receive. Walk and keep walking! Write poetry and prose and essays and long-winded personal emails. Our covenmate Killian suggested that their journal has become an altar, and I think Mary Oliver would relate, and approve.

Mary said:

“I decided very early that I wanted to write. But I didn't think of it as a career. I didn't even think of it as a profession. ... It was the most exciting thing, the most powerful thing, the most wonderful thing to do with my life. And I didn't question if I should - I just kept sharpening the pencils!”

“I never have felt yet that I've done it right. This is the marvelous thing about language. It can always be done better. But I begin to see what works and what doesn't work. I begin to rely more on style, which is, as I say, apparatus or method, than on luck, prayers, or long hours of work. [...] I keep a notebook with me all the time - and I scribble. [...] the angel doesn't sit on your shoulder unless the pencil's in your hand.”

Let’s take some lessons from a best selling poet’s life:

In an interview she said, “it was never a temptation to be swayed from what I wanted to do and how I wanted to live.” In her poem The Journey she expands:

But little by little,

As you left their voices behind,

The stars began to burn

Through the sheets of clouds,

And there was a new voice,

Which you slowly

Recognized as your own,

That kept you company

As you strode deeper and deeper

Into the world

Determined to do

the only thing you could do -

determined to save

the only life you could save.

Mary began writing poetry in earnest at age 14 and did not stop until her death in 2019 at the age of 83. And she won the National Book Award, and the Pulitzer Prize because she just kept writing - awards that cannot come unless the pencil is in your hand.

And let’s all take Mary Oliver’s ghost who haunts me as a role model too. Reach out to people you think you might love, who might love you. Demand attention when you need attention and don’t be shy. Mary may have been reclusive in her lifetime, but in her poetry she is generous with her truths, her honesty, her emotion. So if conversations are hard, try poetry. When life becomes difficult, become a poet. Seek out the beauty in a world that sometimes feels ugly and cruel. Be saved by it, then go and notice someone else. Write love letters to ghost poets. Remember: Mary’s angel called out to me but didn’t sit on my shoulder, didn’t sit beside me, until the pencil was in my hand.

Keep sharpening the pencils.

Mary will continue to be a guide and a balm for me. Months ago I was sleepless the night before a trip to Scotland, my mind flipping randomly with icy fingers through a card catalogue of all the things that could possibly go wrong. So I rolled over and opened my laptop, turning my attention to something more productive than listing travel disasters: beginning my research past the poetry and into the life of Mary Oliver. Almost immediately I discovered the name of Mary’s lover/life partner and a wave of calm and protection washed over me.

When I was 11, my mother, sister, aunt and I went to Ireland on an ancestry seeking mission. One of my most photographic memories of this trip is the bronze statue of Molly Malone - the beautiful, fictional, fishmonger of song, proudly pushing a cart of baskets. For the rest of the trip we sang:

In Dublin's fair city,

Where the girls are so pretty,

I first set my eyes on sweet Molly Malone,

As she wheeled her wheel-barrow,

Through streets broad and narrow,

Crying, "Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh!"

So in the exact moment of seeking refuge from Brittania travel anxiety, the universe chose to reveal to me the fact that Mary Oliver’s love was named Molly Malone. Molly Malone Cook. And my whole body filled with an ancient childlike sense of going home. Of singing songs and exploring the world and everything being just fine… of being alive, alive oh! And it was Mary’s story that brought me to that place of calm.

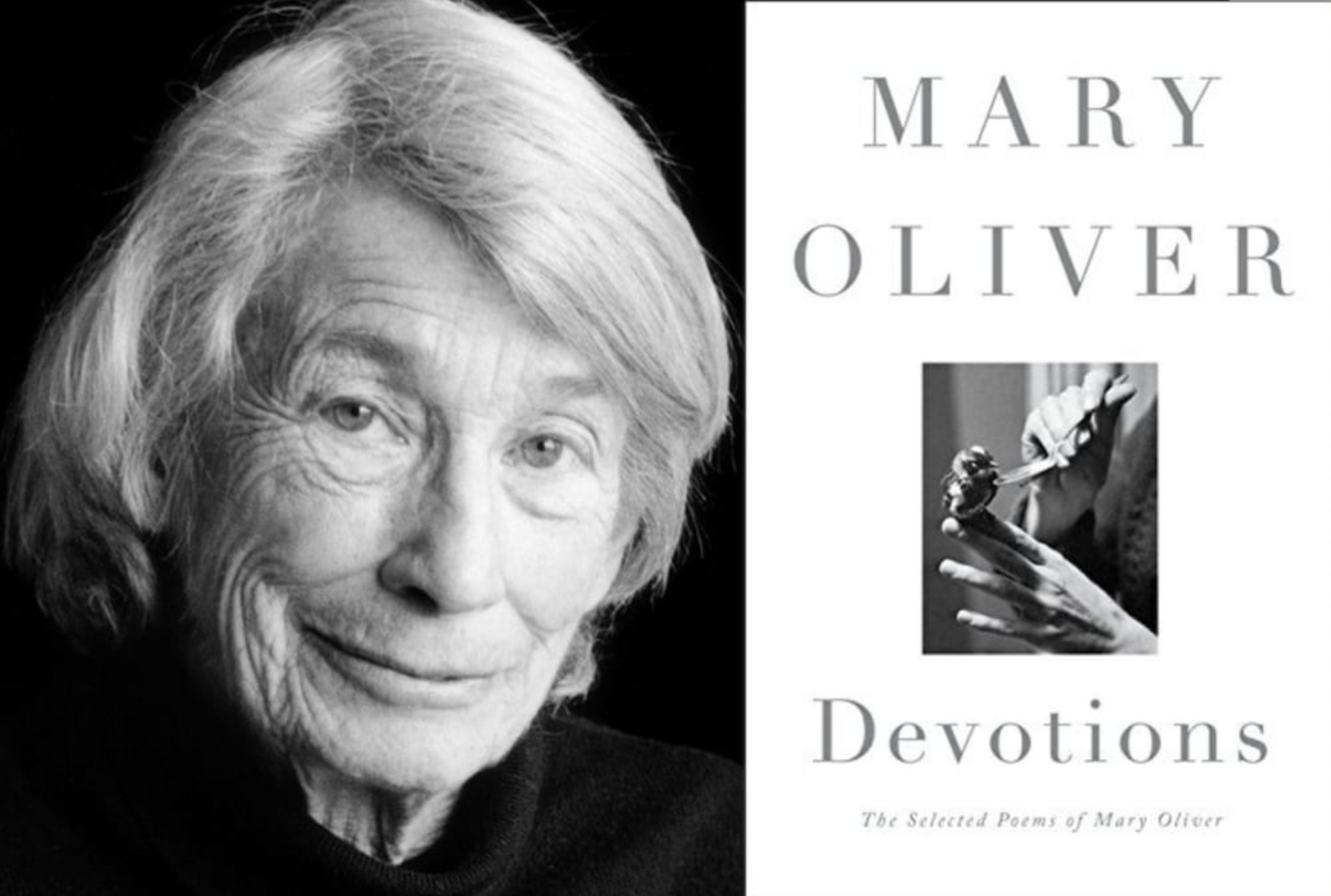

I turn to her in bibliomancy. When I need her advice, I open to a random page of Devotions, a collection of Mary’s poetry which she herself curated after her cancer diagnosis. In a moment of intellectual self doubt, my thumb foraged across the fore-edge of the book and out popped Mysteries, Yes. “Let me keep my distance, always, from those who think they have the answers. Let me keep company always with those who say “Look!” and laugh in astonishment and bow their heads.”

I have a friendship with Mary Oliver. She bestows her wisdom and delivers me from anxiety and I, in return, pay attention.

But more than just attention. Mary told Krista Tipett that attention without feeling is just a report.

“You need empathy with it, rather than just reporting. Reporting is for field guides. And they’re great, they’re helpful, but that’s what they are. But they’re not thought provokers, and they don’t go anywhere. [...] attention is the beginning of devotion.”

She wrote happiness,/ when it's done right,/ is a kind of holiness. Later adding, “appreciation is a very valuable thing to give to the world. And that's the kind of happiness I mean.”

What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? The only life you can save?

Before we leave Mary Oliver today, leave her to be reclusive for a while in the spiritual realm, let’s give some attention, devotion, appreciation and thought-provocation to Mary, and to her most famous poem, Wild Geese. Afterall, appreciation is a very valuable thing to give to the world.

She and we are all friends now, taking our place in the family of things, in this Missing Witches coven.

Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

For a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

– Mary Oliver