In this episode, we tell a story about artist Leonora Carrington. How she found and fostered a new, woman-centered surrealism in Mexico City after the trauma of World War — and after her own incarceration and torture in a psychiatric facility.

We talk with her family, and also meet the art coordinator for Mad Pride Toronto, Molly McGregor, in order to trace lines of kinship between Leonora’s art practice, her vision, and the ongoing global work of imagining and crafting liberation.

In the end, Amy and Risa just chat about the brilliance of Leonora, wishing we could have been in the room with these women, about magic and madness in our own families, and how we have always made circles, found each other around kitchen tables, quilts, and cauldrons.

The full interview with Leonora Carrington’s family will be available free wherever you stream this podcast on Thursday, Oct 6 2022 and the full interview with Molly from Mad Pride will be available on patreon.com/missingwitches

https://www.leocarrington.com/

https://www.instagram.com/leonoracarringtonestate/

http://www.torontomadpride.com/history/

Full Transcript

Leonora Carrington – I Warn You I Refuse To Be An Object

Risa: [00:00:00] The Missing Witches Project is entirely listener supported, and listener, we want you to join us. Do you wanna be part of a community that helps make public research into marginalized ideas? Do you wanna join in interviews with all these magical people and meet other anti-racist, trans-inclusive, neuro queer feminist practitioners of different kinds from all over the world, in our monthly circles? Or, are you maybe just down to send a little money magic towards these stories and ideas and the causes we support? Anyway. Either way, check out missing witches.com to learn more about us, and please know we’ve been missing you.

And one last thing before we start. The stories we tell require a general content warning.

It’s just a fact of this terrain of interrogating what is missing. We promise to hold those moments with care.

[00:01:00]

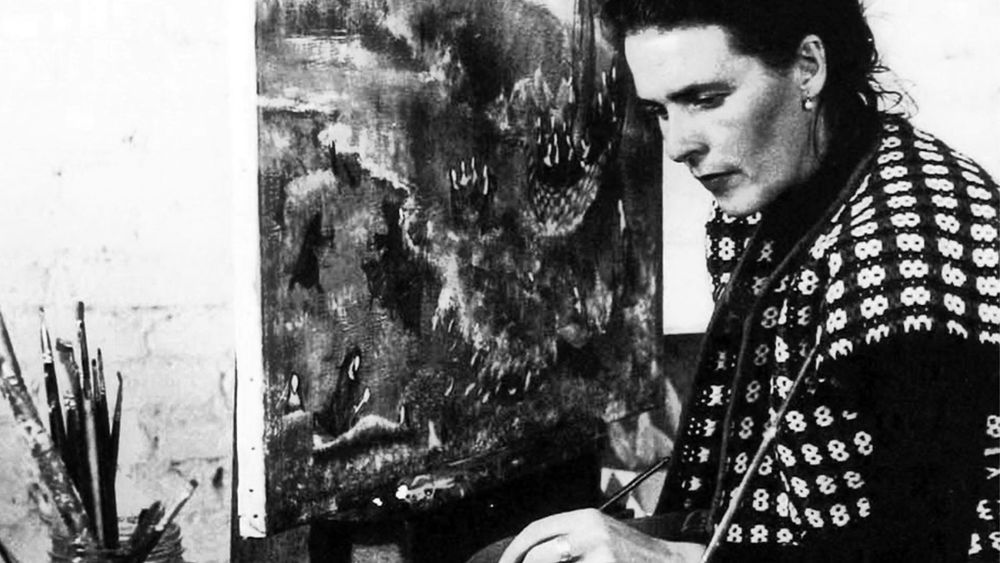

Risa: Leonora Carrington discovered the power of going all the way through. She climbed into the cauldron of her darkest experiences by writing, painting, making dolls and puppets and imagery for her own tarot deck.

Gabriel: She had to rediscover this woman that had been silenced, and she was always looking for what is this, woman like, and she would search this woman, through her painting through her novels, through her interest in witches, through her interest in mythology.

Risa: She met herself in that work and took herself and anyone ready to witness on the journey of all of the way through the journey in the mind, in the perception of reality, the ride of kaleidoscopic changes in the self and the self’s perception of the mysteries constantly around us.

That’s what I feel from Lenora Carrington’s art, that she takes me to the cavern, to the cauldron, to the kitchen table. I feel like gravity suspends and time bends and parts of herself and myself – bee goddesses and priestesses and laughing hyenas smile – in the flickering light. In her novel, The Hearing Trumpet written when Leonard Nora was almost 60, she tells this story.

“Beside the flames said a woman stirring a great iron cauldron

She seemed familiar to me, although I could not see her face(…)

As I drew near the fire, the woman stopped stirring the pot. And rose to greet me.

When we faced each other, I felt my heart give a convulsive leap and stop. [00:03:00] The woman who stood before me was myself.

True. She was less bent than I, and so her form seemed somewhat taller.

She may have been a hundred years older or younger. She had no age (…)

You took a long time to get here. I was afraid you might never come. She said. I could only mumble and nod feeling my age upon me, like a load of stones.

What is this place? I finally asked.

This is hell she said with a But hell is merely a form of terminology. Really, this is the womb of the world when it’s all things come. She stopped and looked at me (…)

And said finally, as if to herself. Old as Moses. Ugly as Seth. Tough as a boot. No more sense than a Skittle. However meat is scarce. So jump in. “

Risa:

She jumps into the [00:04:00] hot cauldron, and when our narrator comes out the other side, she feels refreshed after the hot broth and somehow deeply relieved.

Leonora invites us down to the womb of the world through death to the relief of our real selves.

Her art was a practice of getting into the cauldron of her experiences, living fully in the strange palpitating world of visions that are the truth for her and the truth for all of us. She said,

“I always had access to other worlds. Like we all do. We all sleep. We all dream. That kind of feeling that you had in childhood, that things are very mysterious.

Do you think anybody escapes their childhood? I don’t. ”

Risa: in Lenora’s art practice, she endlessly meets what is possible beyond conformity. She bends linear time to see vast cosmologies. She [00:05:00] wrote, “The duty of the right eye is to plunge into the telescope, whereas the left eye interrogates the microscope” in the preface to the invisible painting. Gabrielle Weiss’s memoir about his mother Leonora. Jonathan PE Burn Rights.

“Carrington’s Art encourages us to live simultaneously in two dimensions, to live not just our ordinary existence, but also in a visual marsh that pulls us in as we engage in creative imaging.

This marsh, like all marshes, is a place of decomposition and new life. Liminal sight between worlds at once, estuary and breeding ground. It marks the meeting point of land and sea of death rot fecundity and rebirth. Let us not forget that Mexico City is built on the ancient Lake Texcoco.

A fundamentally unstable ground trembling with earthquakes. It is bound up in historical as well as geological cycles of death and new life. [00:06:00] This is the terrain of Leonor Carrington’s imagination.

In our full interview with Lenor’as son and grandson, Gabriel Weiss Carrington and Daniel Weiss Argomedo, which we’ll share on Thursday we get their personal perspective on this person they loved so much and are trying with all their might to both share, and to protect.

Gabriel: First of all, she was not a witch. Now this is something that a lot of people want to create and was part of what Danny was saying, a kind of glorifying, an image,

she was interested in witchcraft. She was interested in witches, but it, it, because of this interest, something opens in one, of course, now this opening. Is very mysterious. It, it has to do with understanding [00:07:00] the kind of dark side of the psyche, if you want, but only as Cixous, would’ve spoken about it. Helene Cixous was a very interesting feminist writer.

No? And, and she did speak about the witch, but it’s a very particular witch. It’s a witch that is there to be found and that discovers something within one. And that is the kind of witchcraft my mother was doing continuously.

Risa: Lenora Carrington painted a magical surrealism. She drew in mythic image languages from Celtic Traditions, Buddhism, the Kabalah, Mexican Mayan, and indigenous lore, European goddess cultures esoterica and more. She paints and writes and sculpts with a complex reference and a [00:08:00] sense of humor and a feminist disruptiveness.

The resulting stories and images project a galaxy of her own visionary selfhood. “I warn you, I refuse to be an object,” she wrote, and also this.:”Most of us, I hope, are now aware that a woman should not have to demand rights. The rights were there from the beginning. They must be taken back again, including the mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen, or destroyed, leaving us with a thankless hope of pleasing a male animal, probably of one’s own species.”

Lenora’s life story has to do with taking back mysteries from industrial patriarchs, from the misogyny of the art world, from torture and assault during mental illness. From the terror and fascism of war, and I’ll tell you some of that [00:09:00] here, but pouring over her writing and art and biographies about her, and even during my conversation with her son and grandson, it’s like the iron in my blood gets pulled toward a different focus.

Not to all the times she had to come crawling out, but to a time of friendship and creative life. Shared between powerful women, loving partners, children and animals treated with loving respect, like the friends and wise allies they are.

This is the solace , Venus shining above the trees, a community making together.

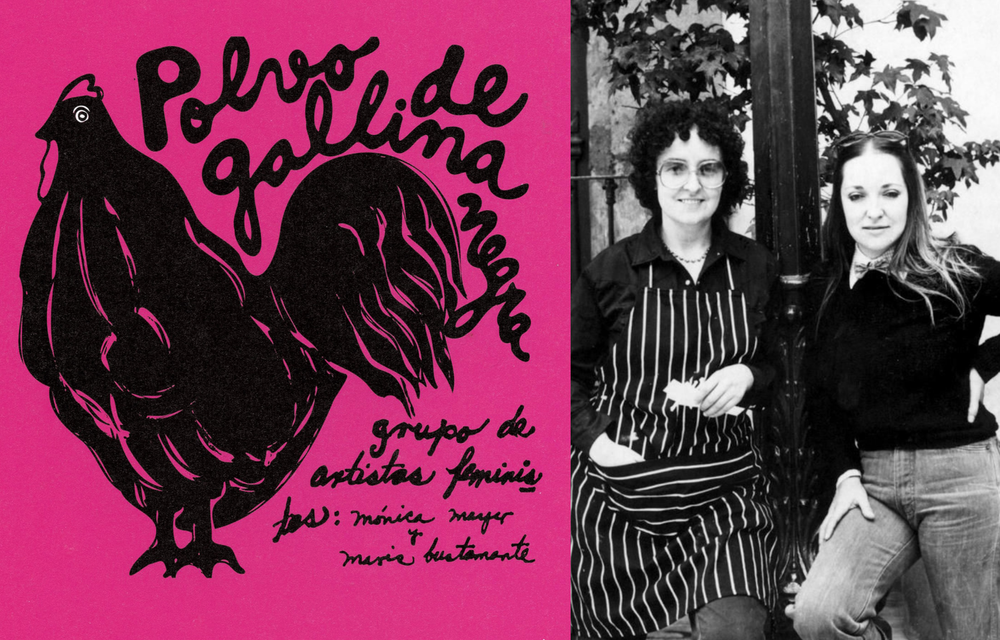

Leonora Carrington. Remedios Varo and their photographer friend, Caddy Horna were very close in the 1950s. Their children grew up together. Carrington worked, she has said with a baby in one hand and a paintbrush in the other. In a hidden corner of Mexico City, Leonard NORAs and Kati took [00:10:00] surrealism to a new place, a place where it was woman-centered and instinctive.

Kati Horna was an anarchist photographer who revolutionized war photography in her early twenties by photographing women, children, and the elderly alongside and within the surrealist detritus of modern life. Puppets and dolls, especially haunted broken toys that war and the exhausting hamster wheel of capital make of us all.

Remedios Varo studied art at a prestigious school in Madrid as a teen and got married and painted and then left her whole life to join the Spanish Revolution. She was imprisoned during the onset of World War and escaped to Mexico. Traumatized but alive. She lived in poverty in Mexico for many years, but made art that is luminous and utterly magical.

She dug into Carl Young, Blavatsky, Eckhart, the Sufis. [00:11:00] She was passionate about the legend of the holy grail, sacred geometry, witchcraft, alchemy, and the I-ching.

Varo described her beliefs about her own powers of witchcraft. In a letter to the Wiccan Conjurer, Gerald Gardner, she wrote, “Personally, I don’t believe I’m endowed with any special powers, but instead with an ability to see relationships of cause and effect quickly, and this beyond the ordinary limits of common logic.”

Add this to the cauldron of the word witch as we like to play with it. An ability to see cause and effect quickly and beyond the ordinary limits of common logic, a doorway that opens something within us. Remedios deserves an entire episode, so I won’t tell you everything I feel about her paintings here because they give me huge feelings.

These sympathetic, glowing women, looking deep into the souls of [00:12:00] cats, meeting out time from the tops of towers that bend the dimensions of the world painted with such mastery, they appear lit from within. These paintings are in conversation with the dimensions inherent in Leno’s paintings, and they’re related in the way I picture these women in conversation.

Exploring, laughing and then finding their own ways to look up close and far away to look past common logic to take back their own mysteries.

I want to just imagine these women together in Leonora’s Kitchen in Mexico City, the things they talked about, the ways they laughed and played. Janet Kaplan wrote “Using cooking as a metaphor for hermetic pursuits, they established an association between women’s traditional roles and magical acts of transformation.”

Leonora made a home [00:13:00] for herself and painted hundreds of images that flicker with a magical life and laughter and acts of transformation.

Susan Aber writes about visiting Leonor in Mexico City, and she describes some of her most straight up mystical paintings in the house opposite A hybrid animal/human female figure sits alone at an altar table set in the central stage like space. With the calm of a priestess, she ingests a ritual meal, an act that provokes transformations in the surrounding pictorial spaces.

We are now in the domain of the feminine sacred, where food production and consumption is a magical act. Sid. Here the white people of the tothe de de none of 1954 portrays the spectral sore services of the ancient Irish fairy race gathered about a table in a communal meal. The chair, dda Toan [00:14:00] and AB AO Quad have as their focus a table upon which a large white egg and arose commingle in an alchemical exchange of milky fluids.

In all of these paintings, the table acts as a doorway between the terrestrial and spiritual worlds, and the kitchen is now both the artist studio and the Alchemist. The full implication of what it means for domestic feminine space to become a cult. Space. Iuse these works with a radical gravitas.

What does it mean for domestic space to become a cult space? What does it mean to see domestic unpaid labor as radical world changing labor? What does it mean to see the places where we actually live our lives as touching the universe? The present moment as a cauldron we can crawl inside of to let our old world old selves die and ize them into the [00:15:00] future.

Susan continues. Harrington was influenced by Mexico’s particular brand of Catholicism where the surviving folk beliefs of the indigenous population merged seamlessly with the canonical Catholicism of the Spanish conquerors. This combination of Paganism and Christianity appealed to her as her own celtic Irish ancestors employed much the same strategy during their forced conversion to Catholicism. It is in this subtler way that Mexico influenced her vision, as she always eschewed, more overt borrowings that smacked of exoticism and appropriation. The dangly draped table, typical of bourgeois households has been slowly reenvisioned as a non-hierarchical meeting ground between women, their animal familiars and the celestial realms.

The paintings feel to me like meeting grounds for different kinds of being across time and space [00:16:00] and other dimensions. Some look like deities, some like microbes. Blink from the left eye to the right and you can travel out along the multiverse. I was deeply delighted and somehow gratified to learn from Leno’s grandson that she had been swimming in string theory before she died.

Like us. She loved the science and magic of the greatest questions in the universe. She liked witchcraft for what it opened up. She was drawn to the witch, as in Ellen Sisu, who writes Now women return from afar, From always from without, from the Heath where witches are kept alive. From below. From beyond culture, from their childhood, which men have been trying desperately to make them forget, condemning it to eternal rest.

The little girls and their ill mannered bodies I mirrored, well preserved, intact unto themselves in the mirror fr ified. But are they ever seething underneath? [00:17:00] What an effort it takes. There’s no end to it for the sex cops to borrow their threatening return. Such a display of forces on both sides that the struggle has for centuries been immobilized in the trembling equilibrium of a deadlock.

Here they are returning, arriving over and again because the unconscious is impregnable. “

Here we are returning over and again, seething underneath. Returning from the places where witches are kept alive. Carrington’s novel. The hearing trumpet in particular sings of the kind of laughing witchcraft I recognize as kin with its old lady, the bearded and dapper narrator. Marion arriving to her wild childhood self freed through the cauldron, finding covin community with elder women who together survive cruel children, and PO is new age men and murderous women too, who wanna protect the narrow [00:18:00] dominance they’ve leaked out by sustaining the status.

Marion’s put away in a surreal landscape that mostly seems surreal in the way that real life is with stupid concrete buildings done up like a birthday cake, a lighthouse like mushrooms for adult women to live in their paint crumbling into weird colors, and she goes through the cauldron and finds herself as the world ends.

That’s a very polls shift, and winter comes to Spain. And the be goddess is returned her holy chaus by seven old ladies and a wolf headed woman and a poet, and things begin anew with a gentleness to animals, new kinds of hearing, and a fire that never goes out.

The hearing trumpet does not embed itself in being anti what came before or anti-anything. Marion’s narrative progresses by being joyfully generative, by asking if the [00:19:00] stories one had been fed might need to be bent into a shape that’s not yet been imagined. The Nora is neither interested in being anti-anything, nor in fitting in.

She is creative, generative, always meeting herself in illusions, in dark corners, in stories, in friendship, in the land beyond where the witch lives. In the invisible painting, Gabrielle, her son writes.

I recall that Le Nora had two visions of herself. The first is a bag lady laid in with large packages and random objects keeping up a nonsensical monologue as she walked the streets of New York. The second, as part of a gypsy caravan on a beautifully decorated wagon drawn by four strong horses.

Leonard Nora saw every journey as a way of seeking out that caravan she’d imagine the scene allowed dreamily voicing the subtle chiming of the bells on the horses moving along a [00:20:00] dusty road

blink, and you miss it. Our shift between these two visions of ourselves, bag lady, and glorious caravan. When Leonard Nora first encountered Max’s ERT art, it struck her heart and decades later she would remember how it felt like a burning inside. She wrote, You know how when something really touches you, it feels like burning?

That burning was a flicker of her future life, of the surrealist art making and storytelling that lay ahead for Leon Nora. And I think following that feeling helped her survive great loss and great darkness. I think for all of us, finding art that makes us burn can fuel our resistance, our resilience, and our delight.

Leonard. Nora was aware of s through his collage. Two children are threatened by a night and Gale. Leonard Nora would say, Ah, I thought this is familiar. I know what this is about. A [00:21:00] kind of world which would move between worlds, the world of our dreaming and imagination.

Leonora refused to talk much about her relationship with Max Ernst, but she was 19 and he was 46 and already married when they met and moved in together. And although they lived “a kind of paradise” for a while, making art and jokes together, he and Andre Britto and other patriarchs of European surrealism conceived of young girls as these marvelously magnetic conductors” belief in the penetrating faculty of youth in the young woman child’s closeness to mystery and sexuality formed the crux of the surrealist doctrine.”

And when Leah Nora wasn’t writing stories and making art, it seemed she was expected to make house for the steady stream of guests who came to visit her. And Ern. And I wanna join with others who have questioned this imbalance of power between them. But I also know Leno wasn’t interested in being a victim or a subject at all.

She was from the [00:22:00] earliest of days, a creator, a maker of her world, a full participant, awake, powerful, alive, making her own choice to leave the new money Victorian hustle of her father’s dreams behind making art everywhere that sang of life. And its unbridled my. Even in the utter trauma of fascist genocidal war, she vibrated with the urgency of life and her own perceiving.

And I know she said Max was the great love of her life and that she was destroyed when he was taken by the gpo and when he was gone with the disease of cruelty, mounting all around her in the small town, she found herself alone in at the edge of war. She got sick. And at her father’s direction, she was imprisoned in a mental institution where she was assaulted and tortured with medications that induced violent mind and body destroying seizures.[00:23:00]

Leonard Nora published her memoir of her psychotic break and of her doctor’s Sadism down under in 1944. It was Andre Barreto who urged her to tell those stories to get them. She told them as a kind of self-guided therapy to work her way through what had violated her and what she wanted to keep of her dissent off the edge.

Later, she would dance with that edge for her own alchemy and art. She describes learning a shifting angle of view and doubled vision and a felt sympathy with all matter without hierarchy. And she kept those visionary abilities, making pictures that communicated what she saw in ways that exceed the written word.

Gabriel: She had to [00:24:00] endure no other people calling her mad and, and she had to suffer, you know, she was inflict to the pond. They, they gave her a drug called cardio soul. That was extremely dangerous and electro shocks and so and so forth.

So, no, it’s not amusing. No, it was not the kind of strange, magical moment that preton speaking about in Naja. Mm-hmm

Gabriel: Art was much more than quote unquote a creative activity. No, it was a restorative activity and a renewal. So she, she also felt that when she was painting, no. Hm.

Daniel: There’s also a historical component behind this word [00:25:00] madness.

Right. And even how it sort of was used to criminalize those that lived differently than us, those that had different sexual orientations. I mean, this was weaponized and to a certain degree still is unfortunately in many places. Right. So I think one also needs to understand the structures of power behind these categorizations, you know?

Molly: my name is Molly McGreer and I am the art coordinator for mad pride in Toronto, Ontario. So I am a mad person. I am bipolar. I was diagnosed in 2015 when I was a student living in Montreal.

[00:26:00] And part of being mad in 2015 is a huge amount of shame for being neuro divergence, having difference of reality.

I started a social work degree to work with people of neurodiversity, and tell my story of recovery. When I was sick, I had a spiritual awakening and I met God for the first time. Right. In a very, I felt like a very real way. and I learned that part of living with psychotic delusions and part of living with neuro changes is absolute magic

and then coming out of living in KMH, I was there for three months against my will, then not against my will. I, up taking a course at X university where I was study social work, in MADD.

I studied under the professor, Jenna Reed, who was an amazing activist in the med community in Toronto, and here I met other med [00:27:00] people and we began to kind of synthesize the experience. It began to have real conversations about it. Um, and I got like a very academic understanding of how madness is not something to be ashamed.

Mad. I felt to be understood and celebrated and critiqued and talked about and found in community. In combination with this work, I began to practice magic. I met people coming outta psychiatric institutions from across, Toronto. And we ended up forming a group where we openly talked about our delusions and began to slowly piece them together and make sense of them in terms of poetry. Because for me, the best way to talk about a psychotic delusion is to compare it to art and creativity.

Last year, I met some really cool activists across the world and found out the mad community is global and there’s a resurgence and I don’t know, low key rebellion against the neurotypical,[00:28:00] all over the place.

And I fell in love with this work. And then in April, I got a little message from someone named Natalie forcep, who was this 19 year old student from Centennial for being, uh, addiction and mental health studies. And she was like, Hey, are seen you posting on these forums. Do you want to start mad pride with me?

Mad pride hadn’t been, um, initiating Toronto since 2017. And so Natalie pulled together me. This got you. And this guy miles, we all have now diversity changes, addiction issues. We’re all like positive people. And we, we drove into organizing full time. we found ourselves sitting in front of CAMH, and you’re sitting and just breathing and watching and imagining how this space could be transformed with art made by mad people. Because I think, I think that art made by mad people is like, like the most beautiful, like it’s [00:29:00] like really pure and, focused and emotional. Magical creations.

Risa: Mad pride and the kind of art making that Molly believes in makes it into the story because madness was in Leno’s life and in her storytelling and in her art.

It wasn’t romantic or fucking fun, but she kept what she wanted of the magic of her other vision, and she refused to let it be destroyed. Mad Pride claims a place in the global work of liberation for those who have experienced mental illness, those who have experienced psychiatric incarceration, those who have survived incarceration in spaces that remain largely unseen in all our [00:30:00] cities.

Mad Pride says you are not broken. Your visions have a place You are allowed to be sick. You deserve community on your way through the rine. We’re all so tired now, these plague years, lunatic with their itchy fingers on the nuclear buttons. Women tortured for showing their hair, the cost of food doubling, and we watch people lining up for hours to kiss a dead queen and the world is madness and we’re sick of keeping a straight face about it all.

We’re very tired and very angry and very sad.

Molly: I think that we are a place where we cannot imagine a society where someone living with psychotic delusions could just be allowed to live with psychotic delusions. Mm. And that we would have a society where we would allow people to just be [00:31:00] sick and we would have the capacity as a community to let.

Get their sickness outta them. Cuz usually people just have to, you know, get their, go to the delusion or the system and be crazy and do their thing before they can come to an understanding on their own that they need help. Or they’re in a position where like they’ve, they’ve harmed themselves and their friends and family lovingly take them to the hospital or the community levelly in there.

And they’re they’re there because they want to be well not because they are forced to take medication and.

I feel like in time, we’re gonna get to a place where these systems of healthcare are actually run by psychiatric survivors. The best work in psychiatric care right now I’ve seen is done by peer support. Because so much of it is getting through stigma and finding empowerment to make choices that are healthy for yourself, because you, you get into rut where you just like you’re at home, you’re medicated, you’re sleeping 18 hours a day. and you forget that you can go [00:32:00] outside.

You forget that. You’re beautiful. You forget how to cook. You forget how to take care of yourself. And you just need someone who’s on your side, who’s been through before. Who’s just like holding your back and saying, you can do it. You can take care of yourself. You can push through this.

You’ve got this, you’ve got this, you’ve got this.

Risa: Molly and Mad Pride make it into the story about Le Nora because these pieces somehow hover together for me, even though they’re not people who ever would’ve interacted in any way. It was Molly alone and so vulnerable that I saw in my mind’s eye when I read Leonard Nora’s description of her experiences in the asylum and down under, and I hear Molly’s voice, the people who supported her, and all the people she supports now in her community social work.

I hear them around the edges [00:33:00] of some of Leno’s paintings and in the stories of Leno and her surrealist. There is a mad magic post-war kinship here between these Toronto teens and the cackling traumatized artists in Mexico City.

Molly makes these massive puppets these days that in their uncanniness and careful craft learned at summers at Bread and Puppet, remind me of Leonard Nora’s puppets and caddy’s photographs. Molly brings her giant puppets to climate protests, and they loom like spirits above the crowd. Whispering. You are beautiful.

You can do this. Art like madness can wash through us, walk through our cells spill past defenses, how art and madness act on us and change what we understand as possible. Exceeds what historians can archive, what politicians can legislate, and that [00:34:00] is a clue to their time traveling power, both art. And sometimes madness can open doors to possible futures,

Can, when held in interstitial communities of care, reroute around the domineering real world to conjure resistance and re-enchantment.

Leonard Nora found her way out, out of Europe, out of incarceration, out of the total grip of sorrow and illness toward a life that, at least within the cauldron of family and friends, cherished her, her vision and craft and selfhood for who she was.

Leonora landed in a community of artists who soaked themselves in the light, stories and other medicines of Mexico. Slowly sweating through the poisons of their war traumas to invent a totally new feminist refugee surrealism.

I see my own grandmother sometimes in Leno’s story, the way her [00:35:00] trauma experience of war blasted her off her feet and fractured her perception. I feel all our ancestors gather close as we gently unravel the threads of what madness. How we can be sick in community with art making as a shared language and lifeline as we manifest liberation.

Molly: In this work. I feel so connected to ancestors, my ancestors are from South Africa.

And they were activists during the apartheid. My aunt Nancy worked with the black slash collective, which is I collected that Nelson Mandela was involved with, And I really feel them in this work. I feel them. I felt them throughout my whole degree.

Like, I’d be writing as an anti-oppression and like crying at my computer, like PM on a Friday night, trying to crank at essays. And I feel them behind me and I’m like doing the work, continue the work, doing the work. And I feel like very supported in a strange way by [00:36:00] these women who are, who are seeking liberation.

And this is I think liberation. This is another form of it, this another, another way of doing it. I feel very connected to my ancestors.

Risa: Leonardo’s cousin went looking for her wayward kin in Mexico and wrote about her life before she died. Joanna Morehead wrote “Varo and Carrington in particular found they shared a deep intensity of Imagin. They encouraged each other. In feats of daring VA would write letters to strangers. Their names picked at random from the phone book, inviting them to attend dinner parties.

-A character in the hearing Trumpet, I feel like is a loving take on Varo. Also writing letters to strangers and ends up being this brilliant investor and crime solver and day saver, thanks to their uncommon logic. -Anyway, Joanna, continue. There were also endless [00:37:00] experiments in cookery with surreal recipes served up to unsuspecting friends, but amid the fun games and tequila, there was serious work being done.

All three women had to earn their own living. Painting was done anywhere in the house where there was space. Frequently with children and animals playing around on the floor far from shackling. Them domesticity seems to have been liberating. Many of Carringtons and Varo’s paintings are set in the interiors of houses, which are transformed into places where extraordinary, inexplicable, exciting things take place.

In carringtons, the house opposite female figures. Move through floors, change into trees, and mix a mysterious potion. In a coran enviros, the creation of birds. A female figure sits painting birds that seem to come to life on the paper and fly out of the window.

Kevin listeners, I hope you carry this from Le Nora and from her circle [00:38:00] when you bring a few trusted ones together around a pot, a kitchen table, and let the mask of conformity slip off your glowing brilliance. Spirit faces and shine with your weird truths, your quick visions. Together, you are part of the great resistance that has always hung down the wires and lay lines of this living world.

Part of the birds that have always been lifting off the page and singing out from our private, domestic magic craft places you can give each other strangeness a safe space and help channel art that changes the world. You are. To paraphrase, Donna Haraway widening the spaces of refuge for each other.

Allow yourselves your madness. Be a loving to it. And also careful. Maybe treat it like those witches coming back from the wild places, because I think the places [00:39:00] where we bend and what we see then and how we hold each other together have something to teach us about this time and about what comes. We can make portals to new worlds when we make art and when we care for each other in our magic and in our madness.

Everybody would always ask Leah, what is that painting? She hated that. Right. She would always throw it back to you and ask you what you saw because you see it’s much more important for her that you become involved in the creative process yourself and understand the importance and value of that creativity to strengthen it’s muscle.

Right? Because that is truly what can change things. And I still truly believe that that is the most valuable thing we can harness in ourselves. Is that creativity.

[00:40:00]

Risa: I love this new format for the podcast where I get to ask you what you think about the person that I wrote about and we just get to talk about it.

I’m so excited to hear what you think about Leno Carrington and Molly and Renada and Caddy Horn at like this whole strange kinship community. I’m really

Amy: excited. Yeah, I made some notes I have some of, Leonard Carrington’s paintings in front of me while we talk, and I just kind of wanna bathe in that, like surrealist space.

Risa: I was pulling some out today too. The. It has different names depending on where you look at it, but the priestess, the scientist with the white birds coming out of her coat is my favorite.

Amy: That’s a good favorite

Risa: It’s so funny to write it and be like, oh we’re going to talk about this. Like the, the [00:41:00] idea of like, uh, she wasn’t a witch. The idea of which open doors for her, you know that her son said

Amy: And I mean, that’s the thing too, like exactly like that’s that we’re not looking for, What label can I take on?

We’re looking for like, what doors can I open and like maybe investigating this word or this. Play space is a way. And, and speaking of which, like there, there were this whole thrust in, in you’re telling of the story was like art and creativity as a place where we can meet ourselves. I love this idea and I think that it.

it ties into surrealism because it is like, like you, I think you said like a, a safe place for strangeness, you know, , when we’re in these creative spaces, it’s a safe place for strangeness. And I think that, like, that how we can meet ourselves in surrealism is [00:42:00] just like an interesting, you know, thought experiment to, to consider.

Risa: Well, and that’s why I felt like it had to be connected to Mad Pride. Even though those movements are so far apart, Mad Pride starts, you know, 1970s Parkdale, Toronto all around the world, kind of flickering in and out as different people take up this cause. But this idea and you know, I call Molly to be like, Tell me about.

I know that you were a part of this. This year. I saw pictures of puppets, like, Just tell me what this is, and she immediately starts telling me, And listeners, if you are members of the Patreon, will have the whole audio of that in interview with Molly up. Um, but she immediately starts telling me about how madness and art by the mad is totally magical. She had to, she had to get sick twice to fully understand what her. Bipolar was teaching her and that like [00:43:00] sitting and being, I call her at one point in the interview, a madness doled. She gets really emotional and feels like really, because she ends up, she finishes her degree in social work and she ends up being that person during Covid that people call to sit with.

Their loved one who’s breaking apart, like flying into pieces to help them get to a place where they choose. And I just love her idea. Like just let, it’s okay to be sick, like the society’s fucking sick. Why do we, why do we lock people away? It’s okay to be sick. How can we make safe spaces to be sick and then make art through that and see it as poetry and see it as prophecy?

Like how do we, how do we. Enshrine it differently.

Amy: Yeah. I, I, I was gonna say frame, but enshrine is a much better, is a much better term. Um, we’ve talked about this a lot over the years, like just trying to change the narrative of how our brains work so that it’s not like, what’s wrong with us? But you know, what, what can we [00:44:00] do?

So many, so many things come up in this space, like, This, this is what art is, right? It’s like a different way of looking at things. And this idea of a, a madness doula, I think is perfect because those of us who have had or are having experiences where they’re struggling with their mental health, we often, it happens in episode.

You know, going through the birth canal or going through the death canal, or coming in and out of this space of, you know, for lack of a better word, madness, , and, and having like a, a, a guide, a non-judgmental guide for that who’s not just pushing you to have a fast birth, but like a healthy one, you know?

Risa: I was really astonished by so much of that, the insights from that conversation with Molly and from, you know, watching these [00:45:00] pieces, Leonard Nora talking about her experience, her incarceration, the violence, all of all of that, the total fucking madness of fascism, right? Like my grandmother.

experienced it in her own ways. I know your father did. Like our families are, we are direct in this direct lineage. Even if we are settler, colonizers, sitting on stacks of privilege, we’re in this direct lineage of global trauma. We’re in this immediate direct lineage of global trauma. Right. Fucking now.

You know, like of course we’re losing our minds. And what does that even mean? Like we’re. We’re not able to just grin and bear it and work another nine to five. Like what does it, what does it truly mean? Like you read Leonard Nora’s down under where she goes back through the experience and her perception is so colorful and hilarious and surreal.

truly surreal, but it’s like, [00:46:00] I don’t know. It kind of makes sense as a response to what she’s living through.

Amy: Right. I mean, if you live in insane times, like if you have been alive and the whole time you’ve been alive, you’ve been hearing, I mean, throughout history since the beginning of time, we’ve been obsessed with the end of the world.

Let’s be clear about that. You know? But the amount of information that we’re getting is just a constant stream of. Just like a meme of like, they’re saying the quiet parts out loud. They don’t even bother with the curtain anymore. And if you’re having like a depressive episode, because the world that you live in, it’s like valid, you know?

Yeah. But it doesn’t mean that you get to step outta the grind.

Risa: Yeah. So what happens to you? You get ground down and then we shatter. Yeah. Or we, we make these communities of care. You know, we, we have faith in these other kinds of communities of care where you can have a safe space [00:47:00] to make your art. that imagines a different world and that reminds you that you’re beautiful and lets you feed yourself.

I, I just love, and I wish I could, I wish there was video. I wish I could be there. And talking with her son and grandson was such a pleasure, but it didn’t give me what I wanted because of course it couldn’t because they’re not in that gang of women. You know? Like, I wanna know what those women talked about when they were by themselves.

These brilliant fucking. Incredible painters. Yeah. And photographers and artists like, And you get a little window of it in the hearing trumpet because two of the characters are very much them. And so you do kind of get like her, her showing you their friendship. I just wish I could have like, hang out in that kitchen.

I mean, she tolerated no bullshit . Mm-hmm. . So I would’ve been terrifying and scathing too, but just to hang out.

Amy: Ugh. But like, what, [00:48:00] what did Leonard Nora and Frieda Colo talk about? Like, Yeah, I would love to know that. I don’t

think

Risa: Fria Col had any fucking time for them. She called them those European bitches, Leonard, Nora Carrington went to her second wedding with Diego Rivera, and I don’t think Fria Collo had any.

It wasn’t

Amy: cool. I still want to

Risa: hear it. Yeah, it wasn’t cool. You know, the framing of that that I’ve heard that kind of makes sense is like they, these like. You know, uh, refugees, European refugees end up in Mexico City and they kind of live a little bit outside the dynamics that still really existed between gender roles in Mexico City.

So the women, these like white, and a lot of times coming from privileged women were kind of. Bitches like to these Mexican women who were like making [00:49:00] Har art and very much involved in a struggle for women’s liberation and Leor Carrington was in the Women’s liberation movement in Mexico. Basically, from the time she got there, she had to leave because it became dangerous to her, her activities in the liberation movement.

She went back, she continued to do it. So she was not a bitch. She was a fucking badass. But I also don’t like, don’t harbor any bad bones at Fri of Cali for being like Ohs European bitches and

Amy: off. What do you know about this place? Yeah, totally. Yeah. Yeah. It’s very real. Very fair, very

Risa: I don’t even know if it’s true. It’s just like that’s like said that she said that, you know? Yeah. Yeah. Like we hear in this interview, like a lot of what circulates, Leonardo Carrington is a very beloved painter in Mexico, but a lot of what circulates about her is bullshit, like including whole, very impressive galleries full of sculptures [00:50:00] that are fakes that are absolutely not hers.

Amy: You know, . But when her name got some cache, then there was money to be made. And yeah. So it goes. Yeah.

Risa: So it goes. So I wanna ask you about this piece, and this is like maybe a little bit of a tie in to next week’s episodes too. We’re gonna talk about Activity Butler. Um, so I’ve been listening to this podcast, with Toshi Reagan and Adrian Marie Brown called Octavia’s Parables, where they basically in each episode tell you what happens in a chapter of one of Octavia’s books, which is Octavia’s books are. I think really fun to read and you can go through them and deal with the horrors that are within them because you are held lovingly by a wonderful narrator, but there’s also some very dark shit.

So if you just want to hear two incredibly wise people just kind of chat about it and tell you what happens. It’s a nice way through the book. Anyway, she ends these episodes. With a [00:51:00] question, and I’m listening to this and thinking about Mad Pride and Leno, and she asks, uh, Adrian asks,” I think I know people who have psychic abilities that the world is not ready for and that they don’t necessarily know how to use or harness.

And I feel like I know some people who are learning to harness. Figuring out how to work with powers that are beyond the norm. And she asks listeners to scan your family and your family histories. Do you have family that always seemed to know things or family members that got locked away or became secret or people called them crazy?

Just think, can you see those people through a different lens of possibility?” So I wanted to pose that question to you in the context of Leno. Are there people in your own family and I, I can talk about people in mind too, that we can look at differently now that you look at differently. Now, are there times that you can [00:52:00] look at differently and think like maybe madness is.

Something akin to magic or like if they had an art practice, magic could have been accessible to them or something.

Amy: My, uh, my grandmother, I mean, it was never talked about,

she apparently had some kind of psychic ability where she just knew things that she couldn’t know, like. One example is like, and again, you know, this was a very long time ago. So if you’re thinking like, Oh, she got a text or saw it on social media or something like, no, that this was before all that. So my mother came home and she had bought a T set and my grandmother was napping.

And apparently if she was very sleepy, that’s when she would let it sort of slip, you know? And my mother said to her, Uh, you’ll never guess what I. And my grandmother sort of sleepily like didn’t open her eyes inside a T set, that kind of thing. Also, apparently, and again, I don’t know much about it because nobody ever talked about it, [00:53:00] and God do I wish that they had talked to me about it.

She was also institutionalized. That she had, I don’t know, I know some things about her physical, like she had thyroid problems and I have thyroid problems, so I. Can guess how she felt and also like this is, Long, long, long time feminist issue of women being institutionalized or incarcerated because of their mental health.

Um, for various and sundry reasons that are mostly. Or often at least about, you know, how they performed their wifely duties and, you know, polite femininity in public and their gastly gastly punishments that women endured for not doing that. And still continue to, to this day, [00:54:00] right now in this very moment that I’m talking.

Um, but yeah, my grandmother was psychic apparently, and institutionalized, definitely. And she was very silent. I know that she had shock treatments, electro shock treatments, which back then were not anything but terrifying for me to think about. But I mean, in, in answer to the question of like, Do I see her differently?

Yes. Because now I imagine when I’m in those places of, of terrible, terrible anxiety, which is the place that I imagine she existed a lot, I can reach out to her. I, I never really got to know her. You know, my grandfather died when I was pretty young, and when he died, she died in all butt body.

You know, she just checked out and she lived for years, but completely checked out. Not a conversationalist before that either . Um, but I don’t [00:55:00] know if that’s because, you know, they lobotomized her with electricity or because she just knew better than to say what she was thinking. I don’t know. And I, and I’m never going to know, but I do.

Feel, you know, I, I’m never gonna know, but I, I have felt that I can go to her when I’m in these places and say like, I know you felt this way. I know you felt this way too. And it’s sort of like, almost like a forgiveness, like when we, when, when we’re. Dealing with our differences of mental health.

And, and I don’t, you know, it’s not a good thing to feel so anxious that you wanna vomit and cry and you can’t, you know, go about the things that you need to do. It’s not a good thing. So I’m not trying to sit here and say like, Yeah, we should all, you know, be seeking out . Um, but it, it’s definitely a different perspective.

It definitely. [00:56:00] You know, some secret pros among the many cons. And again, just to go back to the question, like, yes, I do see her differently knowing that, and sometimes I think that I’m just living a life that she may have dreamt of and, and that makes me feel good, and that makes me feel like.

She is the doula for me in those episodes. Mm.

Risa: That’s such a powerful idea that we are living. Oh these imperfect lives. But they are absolutely lives that women in our families and, and men in our families would have just dreamt of for us. I mean, just beyond even. I think what they could imagine we’re, we’re in these homes that are covered in art.

We have a room of our own. [00:57:00] Mm-hmm. , you know, we write, we’re honest with the people around us. Our sickness and also our magic to whatever degree we choose. I mean, just that alone is beyond I, There’s an ancestor wall behind me with candles lit for this conversation just beyond what those women really could have chosen to talk about.

But I, I love, I’ve been thinking a lot about your chapter in our New Moon book. About the ideas

Amy: coming out next year. Yeah. .

Risa: Um, Just about the idea of the circle, the circle’s everywhere. You know that those women, you know, we, we can use whatever language. It does not bother me if you don’t like the word witch or cove.

Like I don’t care about that . Um, but. They had circles, you know, they, they played card games, they had knitting circles. They cackled with their girlfriends, you know, they were in, my grandmother [00:58:00] was in like a secretary sorority where they swapped vintage teacups. Like, you know, they. They didn’t talk about everything there, but at least there was, there was a place to let down a little bit, Yeah.

Of

Amy: the mask. Um, a movie that I returned to again and again, um, is called, uh, How to Make An American Quilt. Yeah. Did you ever see that movie in the sort of thing? It’s like multiple generations of women who get together to make quilts for special occasions and. It’s just wonderful. I, I love a multi-generational coming of age story.

It’s like Winona

Risa: a rider too, isn’t it?

Amy: Something like that. Oh, it’s Winona Rider. Oh, it’s Winona Rider. But I mean, I don’t want to get too far into Winona Rider’s movies cuz you know, we could, we could do that just because it, it is, it is spooky month after all. And . Yeah. Right. But I do wanna touch on one more thing, which is, You sort [00:59:00] of, I can’t remember if you allude or if you say this exactly, but this, this idea of, of a life being a coldron because, you know, we’re sort of fresh off the heels of, of the autumn equinox and we were talking to kitchen, which is.

And then I started thinking about like, if, if a life is like a cauldron, it’s like a brew. Like when we think of our, our traumas or our joys or, or these things that happen to us as these like monoliths. But if, if I, if we, if you can think of them more as ingredients than. In a cauldron, then we have more agency.

Like if you put too much salt in something that you’re making, you can put in some sugar and magically this like balances out the salt flavor somehow. I still, you know, or put in some potatoes and that’s gonna, and you know, your salt, sugar, and potatoes can be like [01:00:00] witchcraft and therapy as jinx. Monsoon always says witchcraft and therapy.

Or, you know, these circles or, but I just love this idea of a life as a cauldron with like mixing ingredients and, and one of the biggest ingredients is our dna. It’s like these soups in like, you know, ancient Chinese cafes that have been like cooking in the same pot for a thousand years and they just keep adding ingredients and ladling out soup and adding ingredients and label ladling out soup.

So I’m really stuck on that right now. This like, Oh yeah, your life is a, a caldron and there’s so much room for like absurdity and surrealism and like strangeness in there and it’s bubbling. You know, just the visual of it, of pouring ingredients, you know, three cups of joy, , you know, my it. It’s tasting a little [01:01:00] salty.

I need some sugar today.

Risa: Yeah. I need a little

lemon

brighten things up.

Amy: Yeah, exactly. And we, and we’ve all done that. We’ve all tasted something that we were cooking and said like, this needs something and we don’t really know what it is. And so we kind of have to expand. Does it need a little more garlic?

Mm, Add a little garlic. No, that, Oh, it’s acid. And finally you’re like, Oh, that was it. It needed a little acid. And I, I’m just kind of obsessed with like thinking about my life this way. Yeah. I

Risa: love that. I’m definitely that witch in our family. Mark is the chef, but I’m the, when he comes to where he is, like what is the, what is missing?

I like to think I’m good at it, and not just that he does it to make me feel included. Um, ,

Amy: no, but that’s like a, an intuitive, you know, And sensual and sensual

Risa: experience. Yeah. There’s this chef, I like Natasha Picowitz, and she was writing. Um, some people keep, like a bread mother or, [01:02:00] and, uh you know, a mother for a Scooby or whatever, and she’s like, I always keep a soup mother too.

Do other people do this? And so it’s the same idea of what you’re saying, that she keeps every soup a little bit goes into the next soup. Yes. There’s this fermenting and changing and lineage aspect of cooking.

Amy: I love that.

Um, one more quote from Leonarda, I refuse to be an object. Yeah. I think that that’s like, Yeah. I refuse to be an object. Like, I feel like every, which every person that we have ever profiled or spoken to, um, or been in circle with, um, sort of has this sentiment about them.

Risa: It’s like an unfolding idea in my head too, right? Like, I refuse to be an object to myself too. Like at times I wanna like concretize how I [01:03:00] see myself, uh, because I, sometimes I just feel like this. Mass of particles and ideas just like moshing through time and changing and adapting, and doing my best to hold some kind of gravity.

And I’m just like pulling in ideas and letting ideas go and it’s all very wavy and like sometimes I need to look in a mirror and like I said in the last one, like say my fucking name. Say my ancestry, like become concrete in the present. Um, but also to not get too stuck. I think I was stuck for a really long time in some ways.

Like not get too stuck in this one set of possibilities for myself. Like I had to do certain things. I had to make a living, I had to be the provider. I had to, I had to get myself outta debt. I had to get myself outta shit relationships. I had to like do this one job or whatever, like I had to be this one thing.

[01:04:00] And, um, learning how to not be that. Not just, um, object but product. Mm-hmm. , like not be that, that particular tool, like that’s taken some undoing and, and like some crises of faith that I could be something else. Yes. That are ongoing .

Amy: Yeah. One, one of my friends always used the word, um, calcified to describe how she felt, and even when she changed her circumstance, like you say, like it took her a while to become decalcified.

It wasn’t like she, she made the choice and then everything. I mean, everything did change, but , the process was slower. And again, I mean, this is something that we can talk about with chronic illness, physical, mental, slow is okay, and we know that capitalism tells you that it’s not. And we know that you’re a product and that you are a brand and [01:05:00] that you have to monetize every fucking thing that you do to.

Hype in the world, but man, like slow and surreal. Is the tempo . Yes. And I still like, I, you know, I, I have a very supportive spouse, which is amazing. And, and some days I just don’t have it. Some days I just don’t have it. And I’m like, well, time to freak out and beat myself up. And, you know, my spouse is the one who will be like, you know, you kicked ass four days in a row and.

You know, you have a chronic illness and you have to , and I’m like, , Like, you just wanna, it’s, but it’s like banging your head against the wall, you know? Yeah. So if we can be around people who, you know, like Rea and I we’re, we’re not. [01:06:00] Always on our A game, but we have each other to like fill in the gaps. And that’s why like we can have what is a business essentially, but like that feels way outside of capitalism.

Yeah. Because we are there for each other. And sympathetic. Not everybody works in those environments where you can be like, Listen, I just don’t have it today. And your boss is like, I love you. Do you need, you know, like, Yeah.

Risa: Yeah. That’s funny. I think we’ll talk about that more in this class we’re doing for the Bardo, so we’re writing this class on writing, in community writing, in collaboration. Um, cuz Kate be asked us to, and we were like, Oh yeah, that’s what we do. That’s, that’s something we wanna think more about because we do it and. It is so deeply satisfying and healing and successful and like flourishing and full of kindness.

And it’s teaching us different ways to be in community with all different [01:07:00] kinds of people but a huge aspect of it, and this is something you’re talking about with Molly too, is like, Cherishing what you have the capacity for and not resenting when that capacity isn’t there. Like just, we’re not these endless machines.

We, we break apart, we, we fall into. Dis repair. We need to be follow fields. We’re just tired. It’s the new moon. Leave me alone. Like whatever. It’s . And working in true collaboration and working with you has been such a lesson for me in this is like, Like when I collapse, Amy just picks up whatever she can, and when she collapses, I just pick up whatever I can.

Like, there’s no, that’s just what it is. We cancel whatever we feel like we pick up whatever we can. We just do what we can do. We love each other. That’s all.

Amy: I [01:08:00] don’t know. Yeah. Nice. And, and, and we also love you all, our co mates and our listeners. And we love you enough that we’re not just gonna keep churning out stuff until we hate it, until we don’t wanna do it anymore.

And you’re listening, you’re like, What happened? Which just about it sounds like they hate this. I mean, I don’t wanna. That point. I don’t want to get to the point where it feels like, ugh, you know, I have to do another. Like, it’s still a joy. It’s still a joy, Which is amazing too. And we’re so grateful that someone is listening.

In the cauldron of our lives, like, let us gather around. Mm-hmm. , you know, let us gather around those cauldrons of our lives. Like, you know, you don’t have to be the only one putting in ingredients, Lord knows, like we had to take enough ingredients in our lives before we were, you know, grown enough to make our own choices.

And even then, you know, shit happens. But, so you. This notion [01:09:00] of being around a cauldron together, where the contents of the cauldron is like our, our collective work, our collective joy, you know, our collective dissidents, our collective transgressions, and that we’re just trying to make the best tasting soup that we can because we’re all gonna share the soup.

Mm-hmm. .

Risa: And that, that, like, you know, l c Sue, like she calls on women just right. Like we need. You write yourself in the story, you know, like it’s likely a Norris crawling into the caldron to meet herself on the other side, you know, whatever your art practice is. I, I hope you find one play with one, and I hope that like whenever the racism, brutal fucking racism of this world and misogyny.

And you know, this nightmare of seeing women burned and shot for showing their [01:10:00] hair. This, that plays out in different versions over and over again, all around the fucking world. I hope that when you feel the object making force of that mm-hmm. , that there is a place. You know, to widen the spaces of refuge that there is a space that you can make refuge for yourself to meet yourself.

And I, I think that that’s art. I think in poetry you can meet yourself in total abandoned to a writing practice that has no sense or an art practice or to like a kitchen dance. Like flail your, decalcify, your body, if you can flail it or whatever that practice is for you, if it’s ritualized or not, if it’s witchcraft or not, if it’s ancestor conversation or not.

I hope that in those places you feel like you meet, meet some of us around [01:11:00] the cauldron, meet yourself at least, you know.

Amy: Yeah. Bless of fucking me I guess. Bless of Foggy Beat.

Risa: The Missing Witches Podcast is created by Rea Dickens and Amy to rock with insight and support from the Covin at patreon.com/missing Witches. Amy and Rea are the co-authors of missing witches, reclaiming true histories of feminist magic, which is available now wherever you get your books or audio books and of New Moon Magic 13 anti-capitalist tools for resistance and reamp.

Coming fall 2023.